Drugs can relieve pain and cause feelings of pleasure. But they are also dangerous.

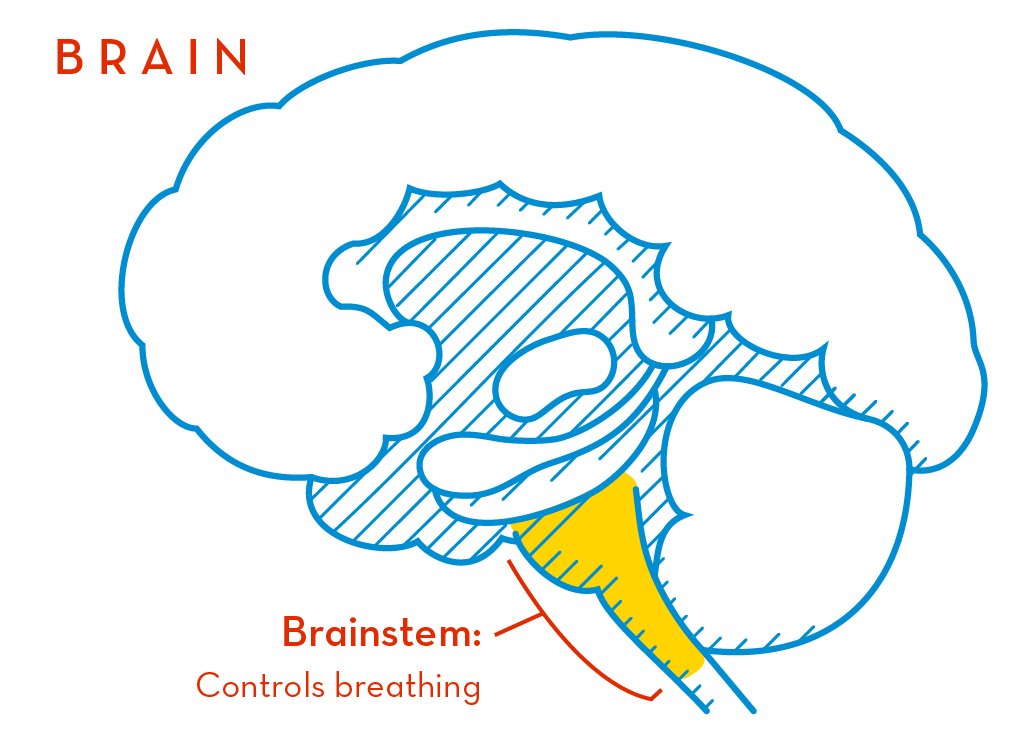

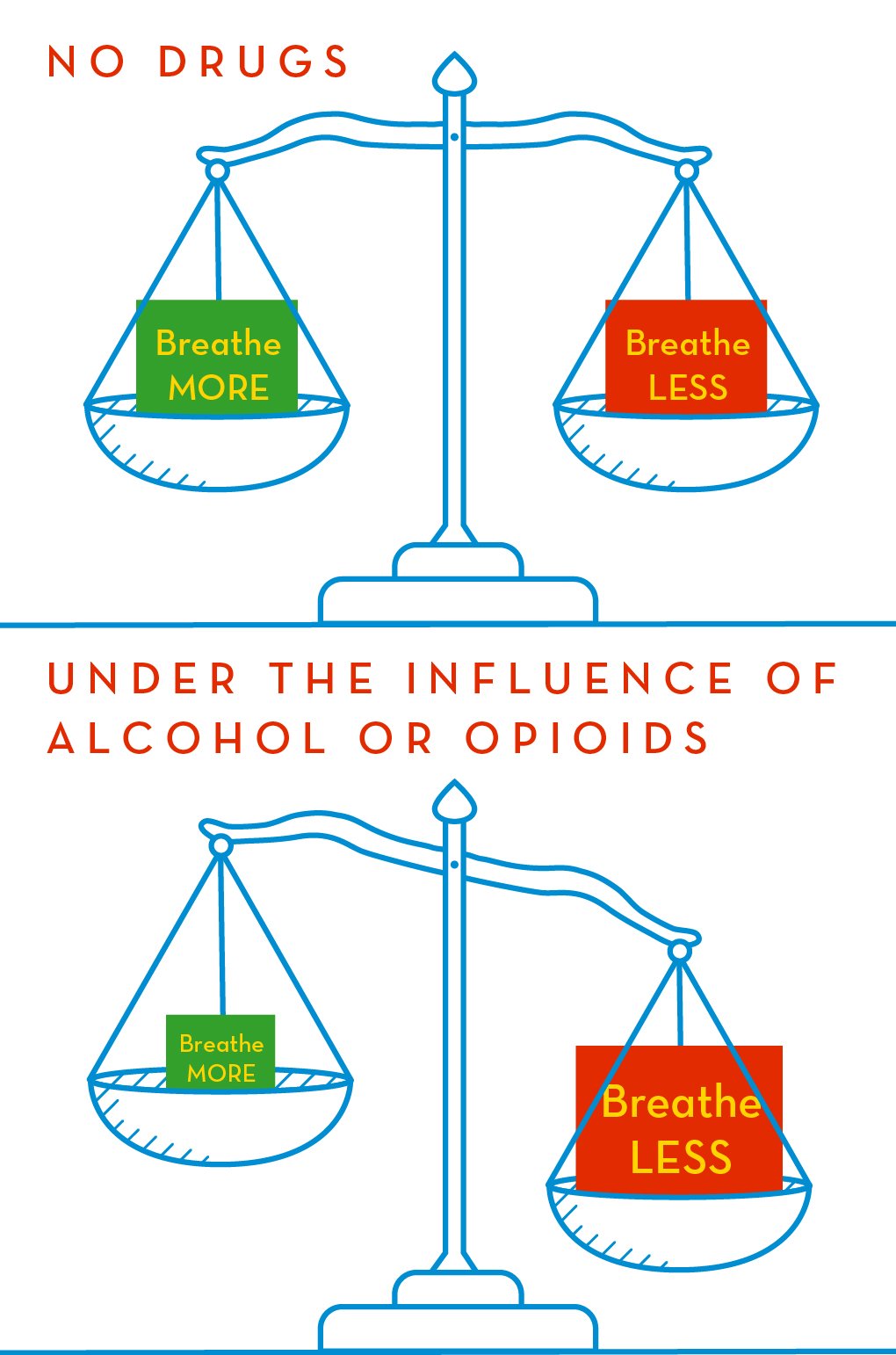

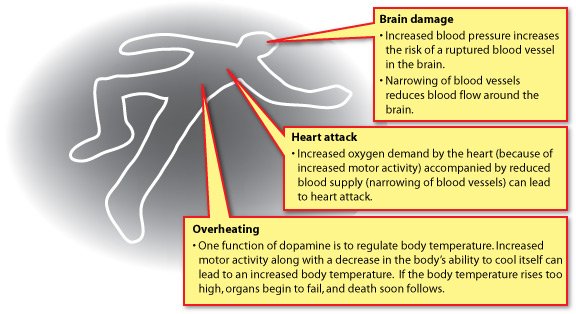

At high doses, drugs can disrupt essential body functions, leading to overdose. In 2013, poisoning (largely due to drug overdose) overtook motor vehicle accidents as the leading cause of preventable death in the United States.

It’s not just people with substance use disorders who are at risk. Anyone can overdose—including first-time and occasional users.

But overdoses don’t have to be fatal. And they can be prevented altogether. Read on to learn what happens in the body during an overdose, key tips for prevention, and what to do if you witness an overdose.

Finding Help

If you or someone you know is suffering from substance use disorder or having suicidal thoughts, help is available:

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Helpline: 1-800-662-HELP (4357)