Genes Affect Your Risk for Addiction

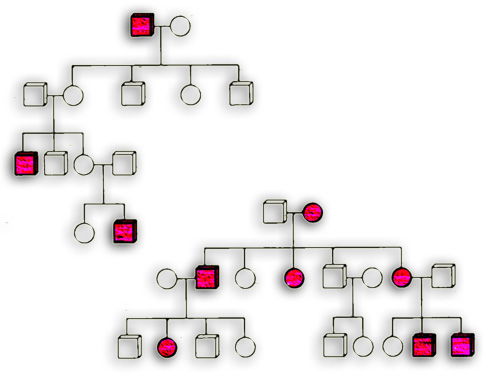

When scientists look for "addiction genes," what they are really looking for are biological differences that may make a person more or less vulnerable to addiction.

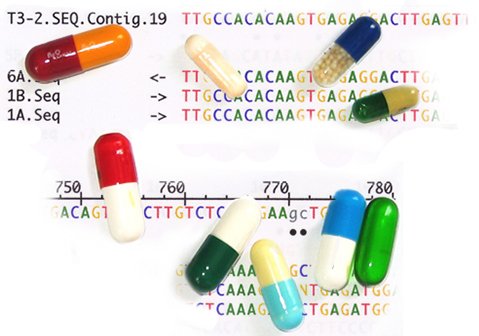

Every person responds to drugs and medications differently. Maybe you’ve even experienced it. Say you take a medication and it works well. But the same pill does nothing for one friend and makes another feel sick. Differences like these are often caused by differences in genes.

When scientists hunt for addiction-related genes, they’re looking for genetic variations associated with these types of responses. A vulnerable person may have a high preference for a particular substance. Or experience extreme withdrawal symptoms if they try to quit. On the other hand, a person is less vulnerable if they feel no pleasure from a drug that makes others euphoric.

“Just because you are prone to addiction doesn’t mean you’re going to become addicted. It just means you’ve got to be careful.” --Dr. Glen Hanson

No one is born destined to develop substance use disorder. Like most other diseases, it’s genes and environment together that determine the risk.