References

Bastiaens, M., ter Huurne, J., Gruis, N., Bergman, W., Westendorp, R., Vermeer, B.-J. & Bouwes Bavinck, J.-N. (2001). The melanocortin-1-receptor gene is the major freckle gene. Human Molecular Genetics, 10(16), 1701-1708. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1701

Medland, S. E. et al. (2009). Common Variants in the Trichohyalin Gene Are Associated with Straight Hair in Europeans. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 85(5), 750-755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.009

Ocklenburg, S., Beste, C. & Güntürkün, O. (2013). Handedness: A neurogenetic shift of perspective. Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.09.014

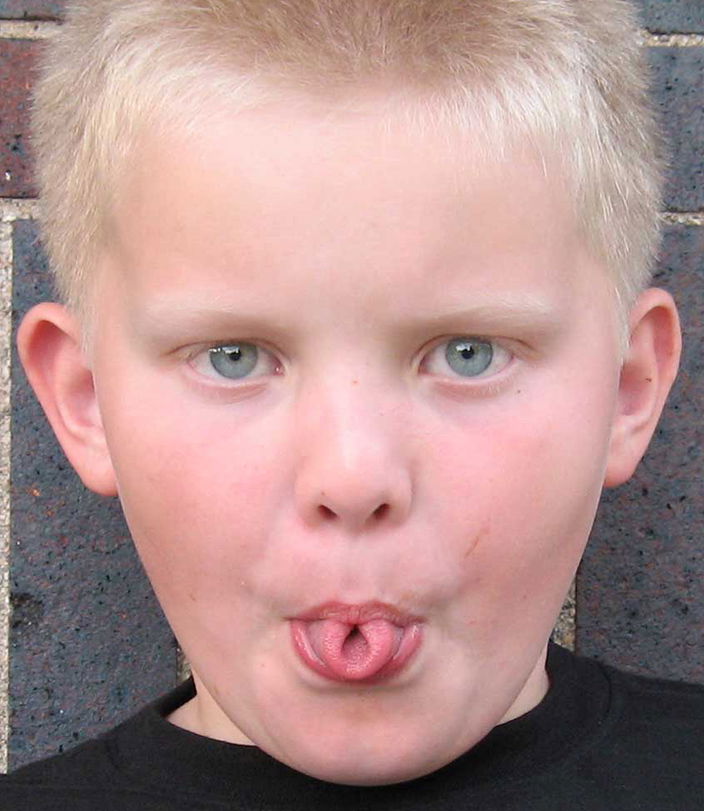

Reedy, J. J., Szczes, T. & Downs, T.D. (1971). Tongue rolling among twins. Journal of Heredity, 62(2), 125-127.

Reiss, M. (1999). The genetics of hand-clasping: A review and a familial study. Annals of Human Biology, 26(1), 39-48.

Sturtevant, A H. (1940). A new inherited character in man. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 26(2), 100-102.

Thibaut, S., Gaillard, O., Bouhanna, P., Cannell, D. W. & Bernard, B. A. (2005). Human hair shape is programmed from the bulb. Cutaneous Biology, 152(4), 632-638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06521.x

Wiedemann H-R. 1990. Cheek Dimples. American Journal of Medical Genetics 36: 376