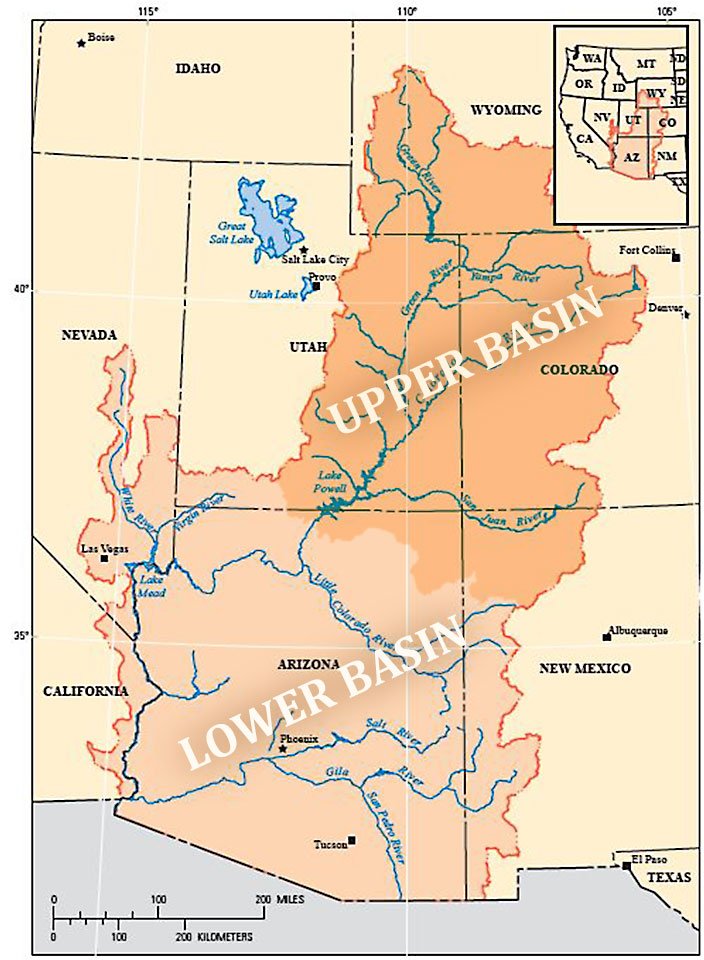

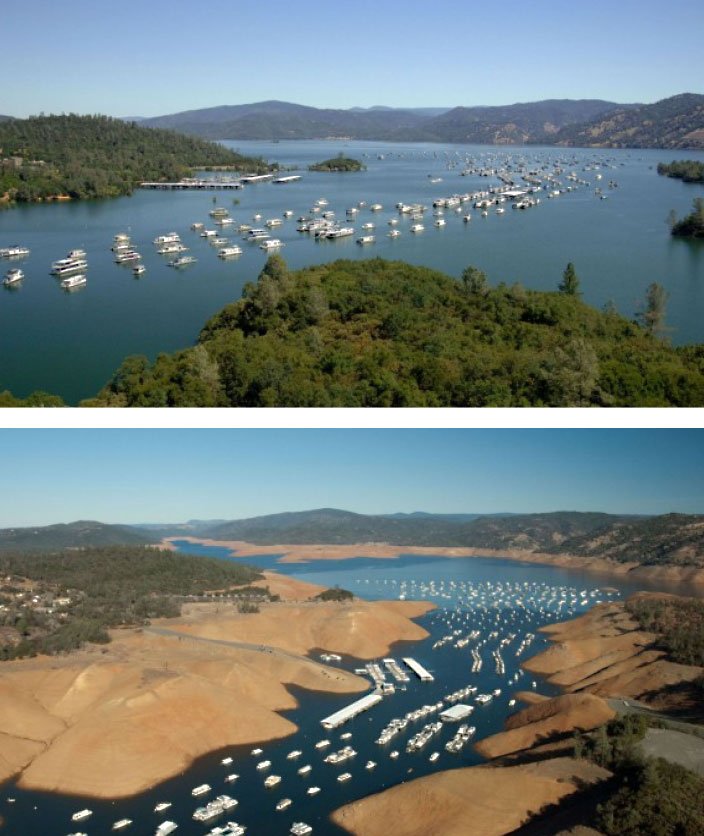

In the coming years, the population in the Intermountain West will likely continue to increase. Projected growth, in combination with a climate that is becoming increasingly variable, raises concerns about whether we will have enough water to meet everyone's needs.

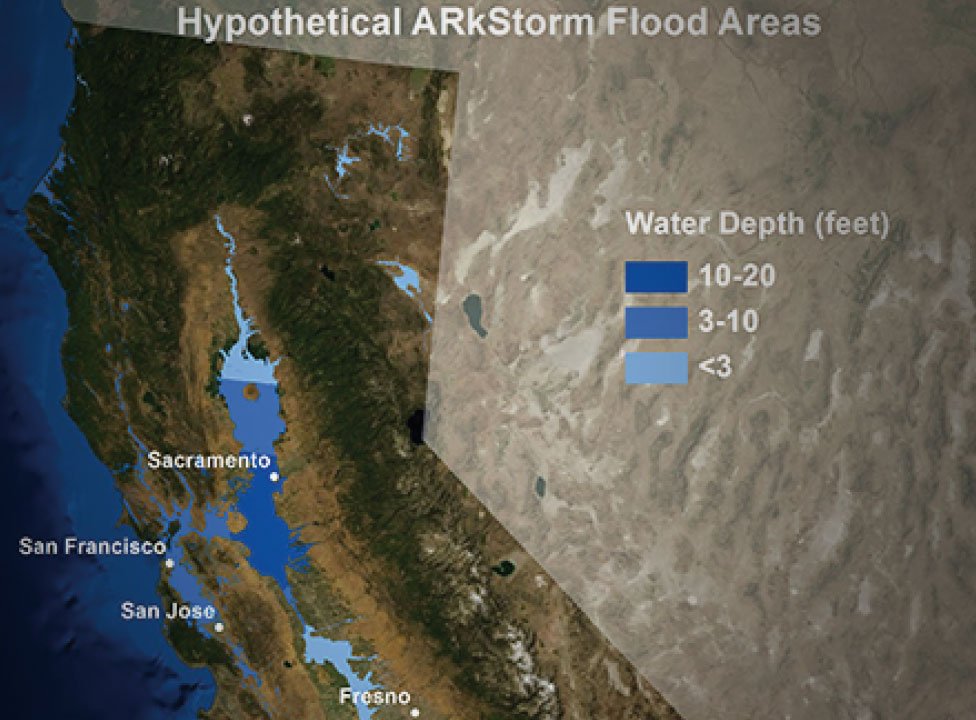

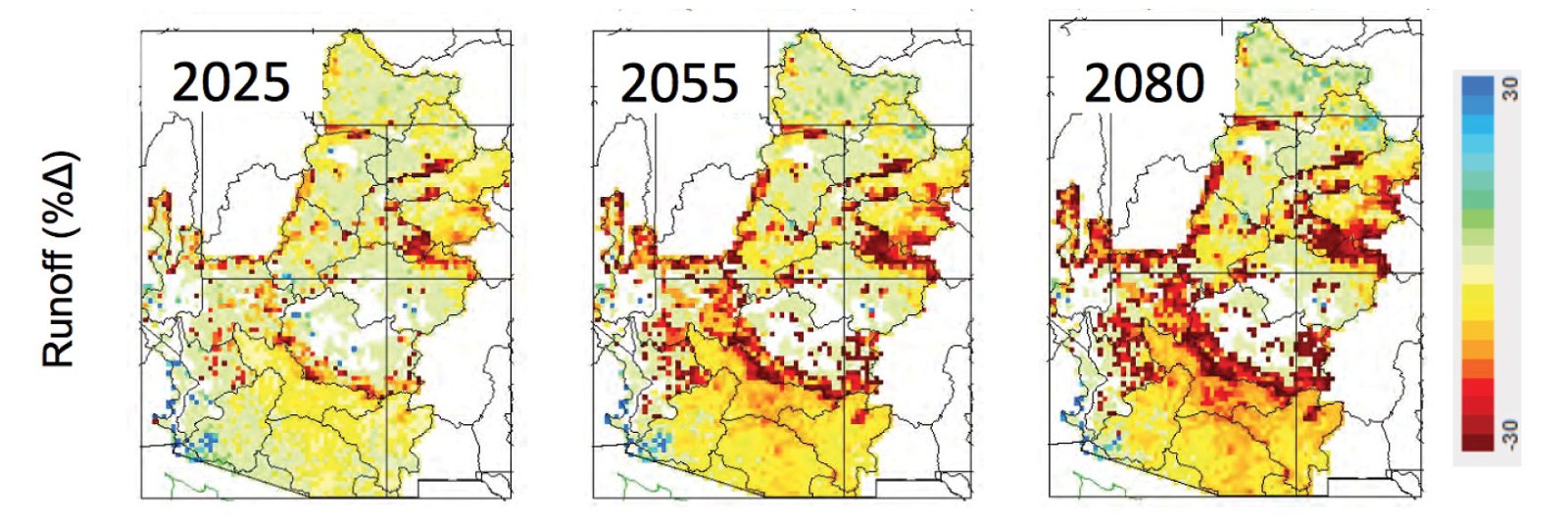

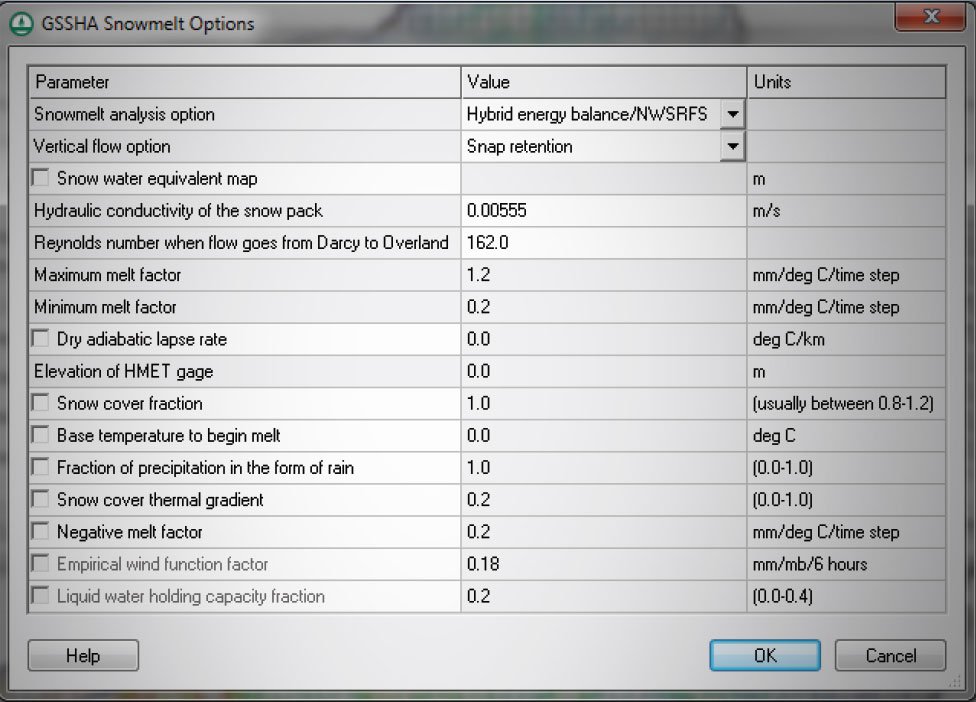

Forecasting models help predict future supply and demand, as well as our vulnerability to disasters like floods and droughts. These models help communities prepare for the future. When communities better understand risks, they can make more informed water management decisions.

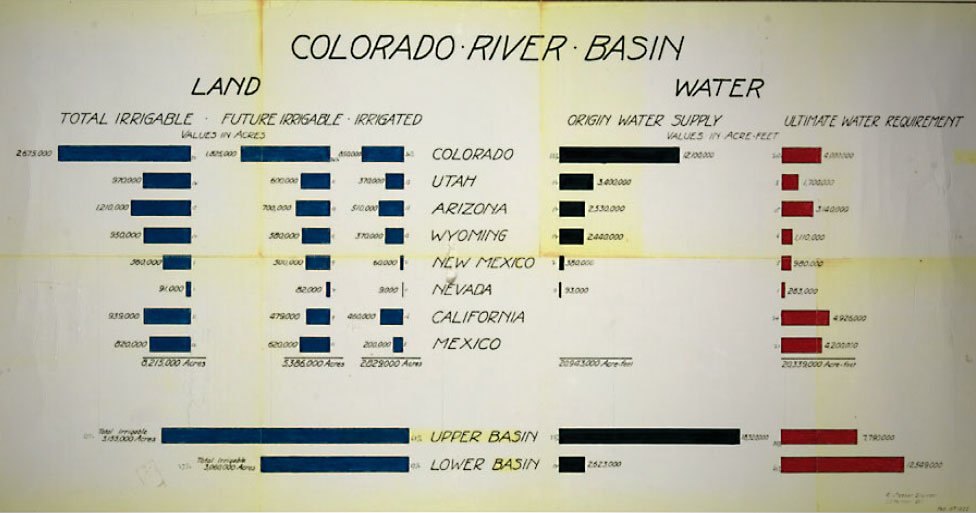

Forecasting water supply and demand is notoriously difficult. Water sources and needs change over time. They are influenced by multiple interrelated factors—like climate variability, population changes, water use policy, distribution technology, economic growth, environmental impact, agriculture demand, and water cost.

As technology and methods advance, forecasts are getting better. But because of the they involve so many dynamic variables, they will always have an element of uncertainty. Water managers can factor in this uncertainty by planning for a range of possible conditions.

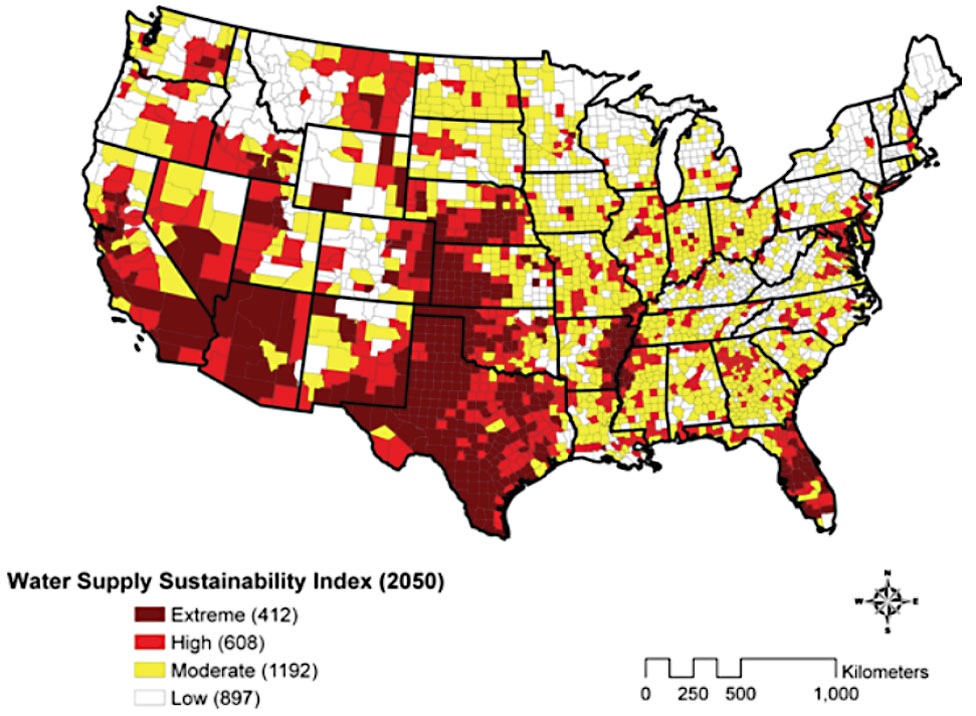

By 2050, our demand for water may outpace supply. This map is a projection based on “business-as-usual” trends in growth, population, and energy demands. It shows the average results from 16 climate models. The darker colors show areas at the highest risk for water shortages if current use patterns continue. In parentheses is the number of counties in each category. Image: “Evaluating Sustainability of Projected Water Demands in 2050 Under Climate Change Scenarios,” Natural Resources Defense Council, 2010