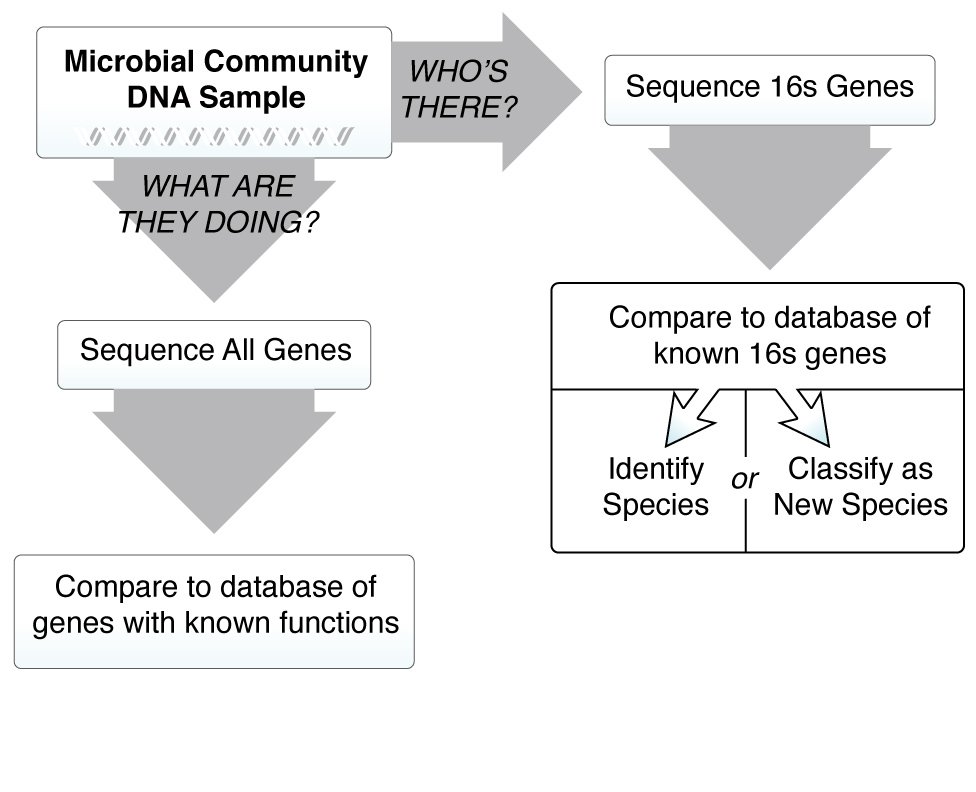

We know the microbiome is important for maintaining human health, and when things go wrong it can contribute to disease. In order to understand how microbes influence human disease, we first need to understand the microbial make up of a healthy person—what types of microbes are present, and what are they doing? These questions are critical, and many research teams around the world are working together to answer them. The more we learn about the microbiome, however, the more we realize there are new questions that need to be asked.

Researchers at many institutions around the world are teaming up to answer important questions about the microbiome: Do humans share a core microbiome? Do relatives or community members have similar microbiomes? How does a person’s microbiome change over the course of a day, a year, or a lifetime?