Take the red-eye from California to New York, and you'll experience firsthand the effects of your body's internal clock. If you feel drowsy or "jet lagged" after the flight, it's because there's been a disruption to your natural circadian rhythms. Your internal clock is saying it's 3 am, but outside, it's time for breakfast.

Living organisms evolved an internal biological clock, called the circadian rhythm, to help their bodies adapt to the daily cycle of day and night (light and dark) as the Earth rotates every 24 hours. The term "circadian" comes from the Latin words for about (circa) a day (diem).

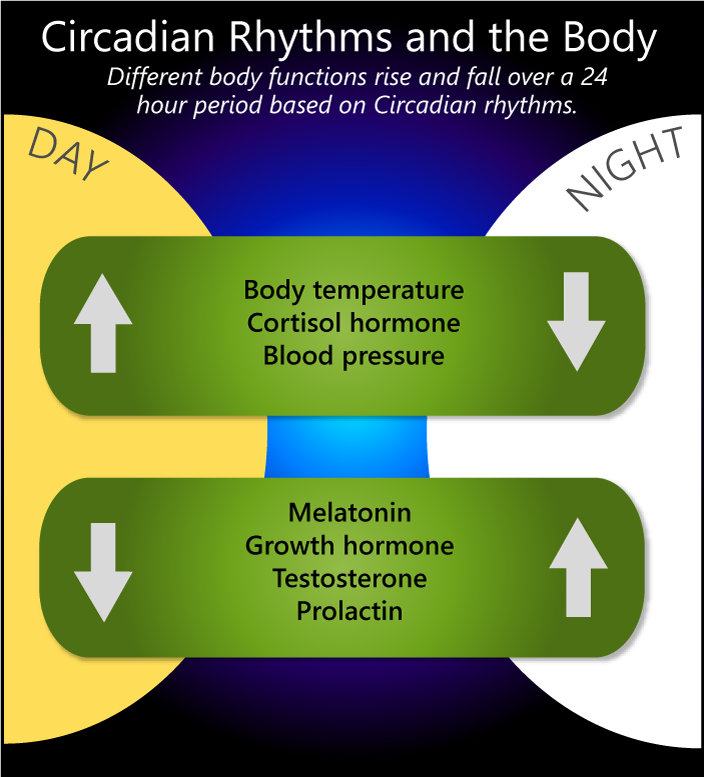

Circadian rhythms are controlled by "clock genes" that code for clock proteins. The levels of these proteins rise and fall in rhythmic patterns. These oscillating biochemical signals control various functions, including when we sleep and rest, and when we are awake and active. Circadian rhythms also control body temperature, heart activity, hormone secretion, blood pressure, oxygen consumption, metabolism, and many other functions.

Daily cycles also regulate the levels of substances in our blood, including red blood cells, blood sugar, gases, and ions such as potassium and sodium. Our internal clocks may even influence our mood, particularly in the form of wintertime depression known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

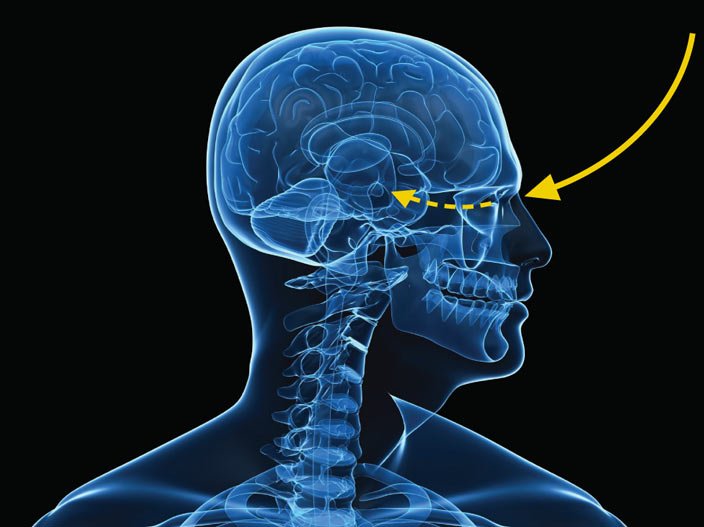

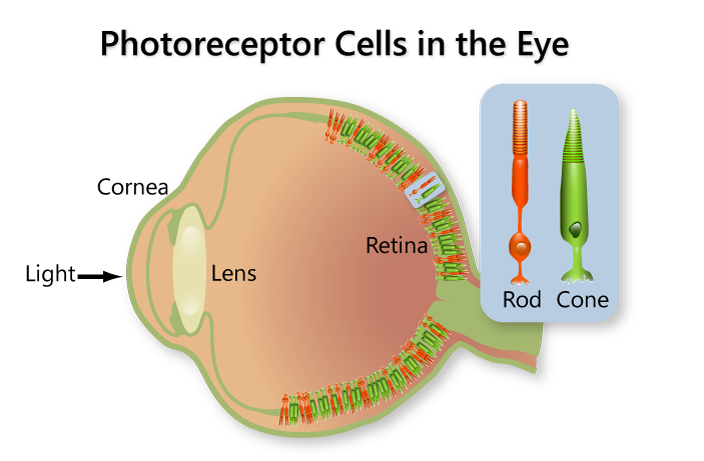

A biological clock has three parts: a way to receive light, temperature, or other input from the environment; the protein and chemicals that make up the clock itself; and components that help the clock control the activity of other genes.

In the last few decades, scientists have discovered the genes that control internal clocks: period (per), clock (clk), cycle (cyc), timeless (tim), frequency (frq), doubletime (dbt) and others. Clock genes have been found in organisms ranging from people to mice, fish, fruit flies, plants, molds, and even single-celled cyanobacteria.