Every organism has a unique body pattern. Although specialized body structures, such as arms and legs, may be similar in makeup (both are made of muscle and bone), their shapes and details are different. While an embryo grows, arms and legs develop differently due to the actions of homeotic genes, which specify how structures develop in different segments of the body.

Homeotic Genes and Body Patterns

How did scientists discover genes that determine body pattern?

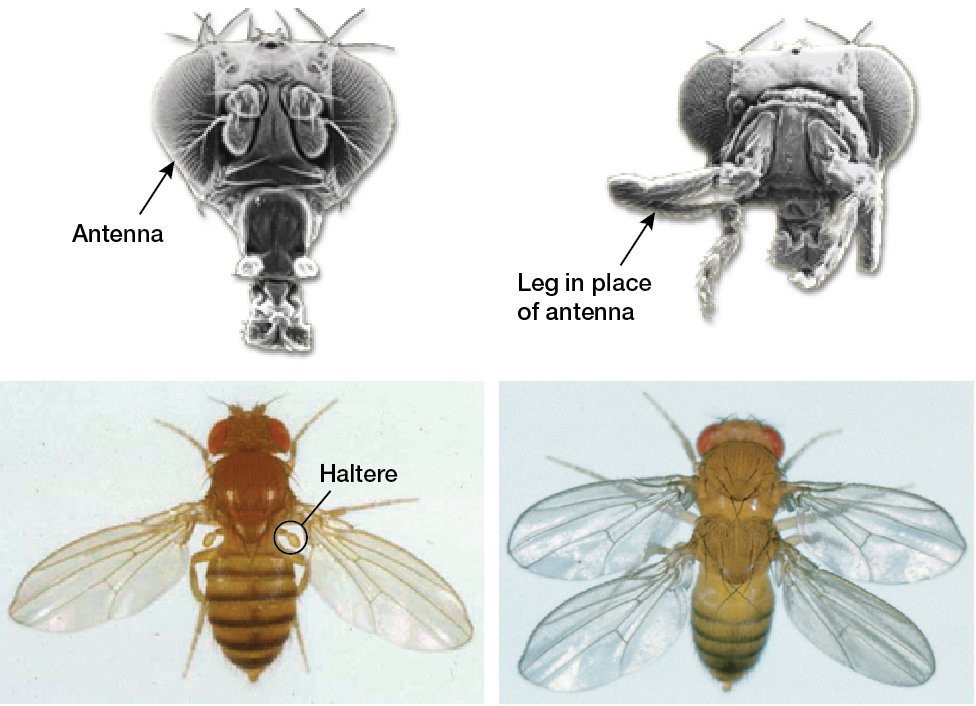

Scientists discovered homeotic genes by studying strange transformations in fruit flies, including flies that had feet in place of mouth parts, extra pairs of wings, or two pairs of balance organs (called halteres) instead of wings. Some even had legs growing out of their heads in place of antennae!

Scientists called these modifications "homeotic transformations," because one body part seemed to have been replaced by another. Researchers, including a group headed by Ed Lewis at Caltech, discovered that many of these transformations were caused by defects in single genes, which they termed homeotic, or Hox, genes.

This work demonstrated that antennal cells carry all of the information necessary to become leg cells. This is a general principle: every cell in an organism carries, within its DNA, all of the information necessary to build the entire organism.

Top: (Left) Normal fruitfly; (Right) Fruitfly with mutation in antennapedia gene Bottom: (Left) Normal fruitfly; (Right) Fruitfly with a homeotic mutation that gives it two thoraxes. Bottom images courtesy of the Archives, California Institute of Technology.

Shared characteristics

Genes in different organisms that share similar sequence and function are called homologous genes.

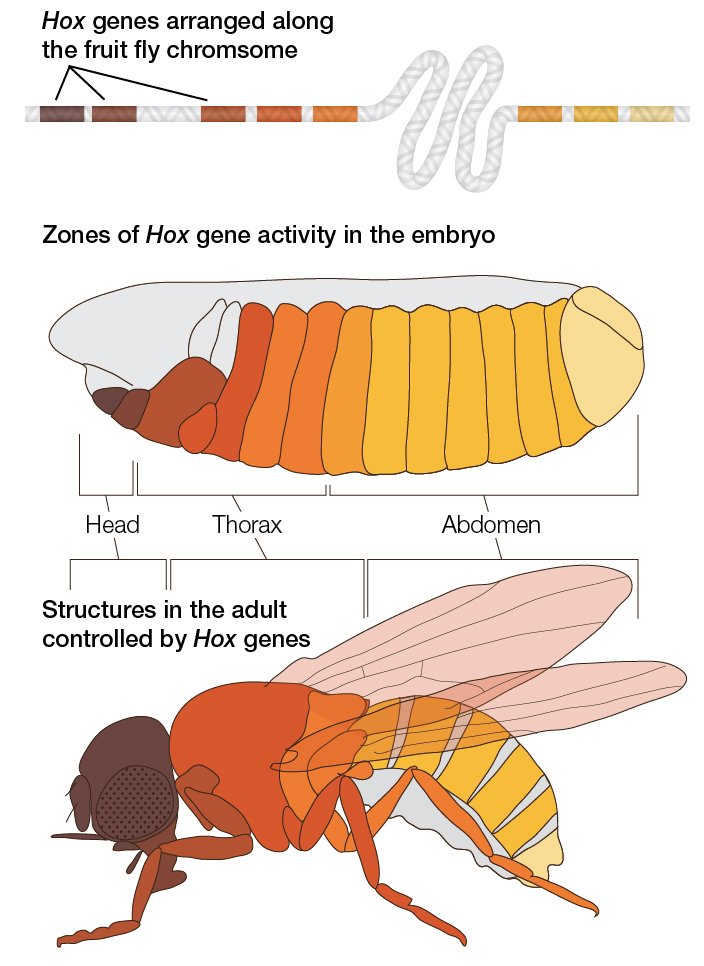

Fruit flies begin life as worm-like creatures made up of repeating units, or segments. Early in development, Hox genes are switched on in different segments. Patterns of Hox gene activity give each segment an identity, telling it where it is in the body and what structures it should grow. For instance, genes that are active in the head direct the growth of mouth parts and antennae, while genes that are active in the thorax direct the growth of legs and wings.

Changes to Hox gene expression change a segment’s identity. For example the first segment of the thorax normally grows legs, the second grows legs and wings, and the third grows legs and halteres. When the Hox gene activity in the third segment is made the same as that in the second, both segments grow legs and wings (see photos above).

While studying the DNA sequences of homeotic genes in fruit flies, researchers found that they all shared a similar stretch of about 180 bases; they named this stretch the homeobox. The homeobox is just a portion of each gene. If the words below were homeotic genes, the capital letters would represent the homeobox: togeTHEr - THEoretical - gaTHEring - boTHEr

Researchers used DNA-sequence similarity to find genes with homeoboxes in other species, including other insects, worms, and even mammals. Together, these genes make up the Hox gene family (Hox is short for homeobox).

Interestingly, Hox genes are arranged in clusters. Typically, their order on the chromosome is the same as the order in which they appear along the body. In other words, the genes on the left control patterning in the head, and the genes on the right control patterning in the tail.

Genes hold clues about evolutionary relationships

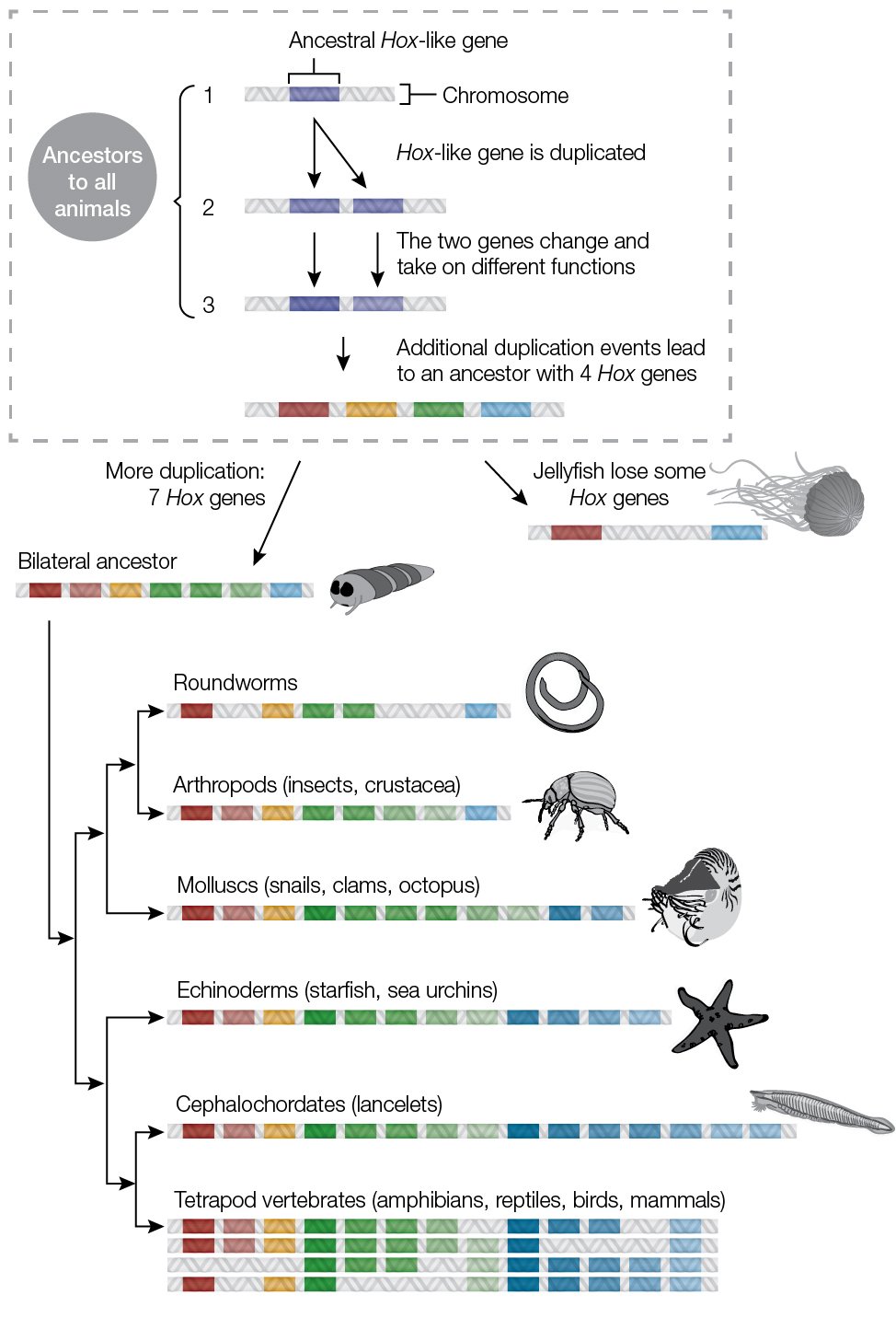

Nearly every animal that's been tested has homeobox sequences in its DNA, suggesting that Hox genes arose very early in the animal family tree. Genetic sequences maintained over evolutionary time are thought to be especially important to the basic development of even distantly related organisms. The presence of homeotic gene sequences in animals as different as jellyfish, insects, and mammals suggests that these genes have a crucial function in many, and perhaps all, animals.

Scientists have studied the genes' DNA sequences, functions, and organization to learn about evolutionary relationships. Hox genes have revelaed many clues about the evolution of the animal family tree.

The similarities among Hox genes, especially in the shared homeobox sequence, suggest that they all arose from a single ancestral gene that was duplicated multiple times. After each duplication event, the genes gradually changed, taking on slightly different jobs. This process is known to evolutionary biologists as "duplication and divergence."

The first duplications happened a very long time ago. An animal that lived about a billion years ago, the ancestor to all animals, had at least 4 Hox genes. By 600 million years ago, in the ancestor to all modern animals that have bilateral symmetry, the number grew to at least 7. We know this because animals descended from this ancestor have homologues of these genes.

Additional duplication events happened in some branches of the animal family tree. In insects, for example, a gene near the right end of the cluster was duplicated. In vertebrates, the entire Hox cluster was duplicated—three times in mammals and up to 8 times in some types of fish. The duplicate genes were then free to take on new functions, often leading to more-complex body structures.

Like other genes, Hox genes are more similar in closely related species and less similar in more distantly related species. By comparing sequence similarity, scientists can determine when in evolutionary history certain duplication events happened, and where some Hox genes were lost along the way (additional gains and losses have happened within individual species in each group).

Illustraiton based on information from Pascual-Anaya et al (2005), Carroll et al (2005), and Garcia-Fernandez (2013).

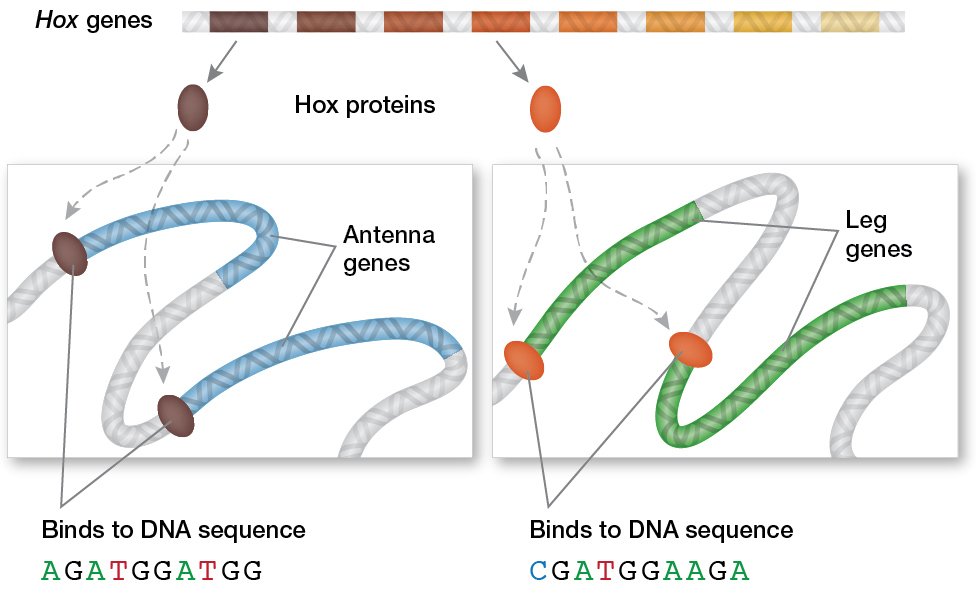

Hox proteins regulate other genes

Hox genes code for proteins that attach to molecular switches on DNA, turning other genes on and off. The DNA-binding piece of a Hox protein is called the homeodomain, and it's encoded by the homeobox. The homeodomains in different Hox proteins are similar but not identical—they bind to different DNA sequences. So different Hox proteins regulate different sets of genes, and combinations of Hox proteins working together to regulate still other sets of genes.

As regulators of other genes, Hox proteins are very powerful. A single Hox protein can regulate the activity of many genes. And sets of genes work together to carry out "programs" during embryonic development—programs for building a leg or an antenna, for example—much like computer programs carry out specific tasks.

Homeotic genes and evolutionary change

A large amount of animal diversity is built on two simple ideas: bodies made up of repeating units (or segments), and genetic programs for building structures.

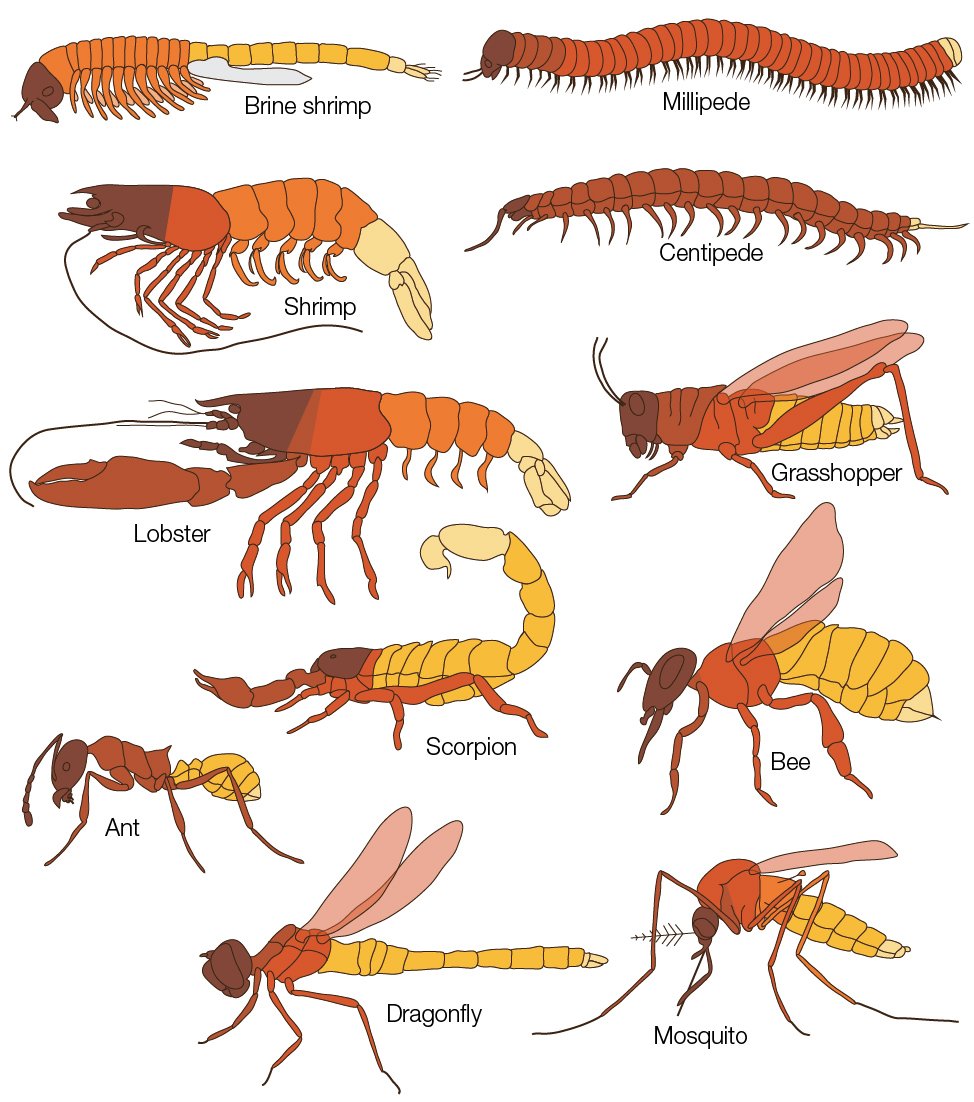

Just within arthropods (shown on the right), variations on this theme have given rise to an enormous diversity of body types. And in fact, in many cases, domains of Hox gene activity parallel the different types of structures that grow out of the animals’ body segments.

The bands of color highlight body segments that have similar identities; you can think of each color as running a different genetic program: a “leg” program or an “antenna” program, for example. Once a program exists for building a structure, it can be reused elsewhere simply by shifting Hox gene expression. It’s easy to see how adding some segments and running the “leg” program in them can build an organism with a few more sets of legs.

And the genetic programs themselves can be modified (through changes in the “leg” or “antenna” genes) to build structures that are a little different. For instance, the “wing” program didn’t come about from scratch—it’s simply a modified “leg” program.

A genetic change that leads to a change in body shape might allow an organism to capture food more effectively or avoid predators, giving it a reproductive advantage. Its genes may be preferentially passed along to the next generation, thus influencing the course of evolution.

Vertebrate Hox genes

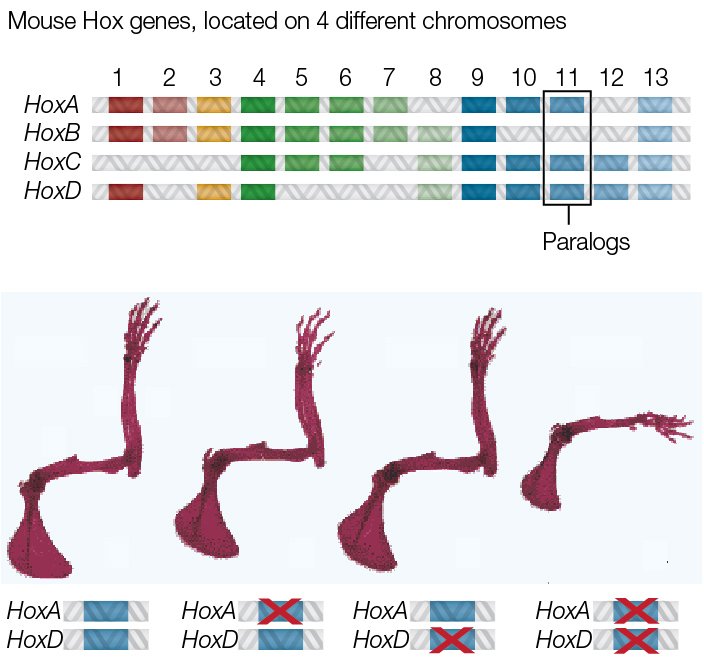

In vertebrates (animals that have backbones), the entire Hox cluster has been duplicated multiple times. Mice and other mammals have four Hox clusters. All four are similar, but each is different. Similar genes in different clusters are called paralogs.

Most paralogs have partially overlapping functions, so figuring out how Hox genes function in vertebrates a challenge: the effects of changing a single gene are often hidden by functioning genes in the same paralogous group. But changing the function of multiple genes in the group can have dramatic effects.

The photos on the left, provided by Mario Capecchi's research group at the University of Utah, show mouse forelegs. Inactivating one paralog or the other has subtle effects (middle two images). But inactivating both makes a dramatically different limb (right). This experiment and others have shown that Hox genes in mice work much the same way as they do in fruit flies.

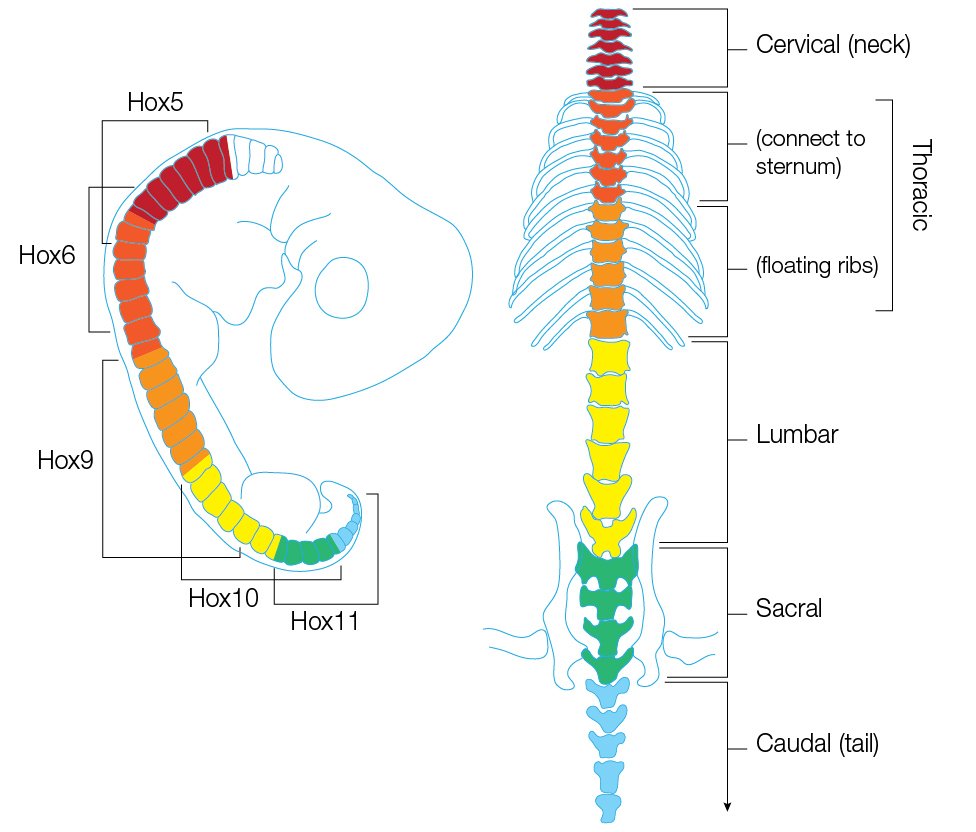

Hox genes direct the identity of vertebrae

While mice and other vertebrates are not as obviously segmented as arthropods, certain regions of their bodies actually are. Vertebrae, with all their associated muscles and bones, grow from repeating units in the embryo called somites. Hox genes (often in combination) help define somite identity, directing them to develop differently depending on where they are in the body.

Just like Hox genes in arthropods direct segments to grow legs, wings, or antennae, Hox genes in vertebrates direct segments to grow ribs (or not) or bones that fuse together to form a sacrum.

Experments in mice show how Hox genes affect vertebra identity. In mouse embryos, the Hox10 genes turn the “rib” program off. The genes are normally active in the lower back, where the vertebrae don’t grow ribs, and inactive in the mid-back, where the vertebrae do grow ribs. When the Hox10 paralogs are experimentally inactivated, the vertebrae of the lower back to grow ribs. Something similar may have happened in nature. In snakes, Hox10 genes have lost their rib-blocking ability, which may be why they grow ribs from head to tail.

Hox genes play many more roles in vertebrate development. They help specify the difference between an arm and a leg, as well as a pinky and a thumb. In the nervous system, their expression in segmented embryonic structures called rhombomeres directs the development of different brain regions.

Hox genes are a fascinating example of how a single gene that did something well was copied and re-purposed through evolution to do even more.

(Left) Mouse embryo showing somites; (Right) Adult mouse vertebral column. Colors show vertebrae with different identities. Regions of Hox gene activity are shown with brackets on the embryo. Based on images in Wellik (2007).

References

Carroll, S.B., Grenier, J.K. & Weatherbee, S.D. (2004). From DNA to diversity: molecular genetics and the evolution of animal design (2nd ed.). Malden, MA ; Wiley-Blackwell.

Davis, A.P., Witte, D.P., Hsieh-Li, H.M., Potter, S.S. & Capecchi, M.R. (1995). Absence of radius and olna in mice lacking hoxa-11 and hoxd-11. Nature, 375, 791-795. doi:101038/375791a0

Garcia-Fernandez, J. (2013). The genesis and evolution of homeobox clusters. Nature Reviews Genetics 6, 881-891. doi:10.1038/nrgl723

Heffer, A. & Pick, L. (2013). Conservation and variation in Hox genes: how insect models pioneered the evo-devo field. Annual Reviews in Entomology, 58, 161-179. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153601

Lews, E.B. (1978). A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature 276, 565-570.

Mallo, M., Wellik, D.M. & Deschamps, J. (2010). Hox genes and regional patterning of the vertebrate body plan. Developmental Biology, 344, 7-15. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.024

Pascual-Anaya, J., D'Aniello, S., Kuratani, S. & Garcia-Fernandez, J. (2013). Evolution of Hox gene clusters in deuterostomes. BMC Developmental Biology, 13(26). doi:10.1186/1471-213X-13-26

Pearson, J.C., Lemons, D. & McGinnis, W. (2005). Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nature Reviews Genetics, 6, 893-903. doi:10.1038/nrgl726

Wellik, D.M. (2007). Hox patterning of the vertebrate axial skeleton. Developmental Dynamics, 236, 2454-2463. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21286