Virtually every plant that is grown for food, fiber, or other purposes has been improved through selective breeding.

To domesticate crops, farmers saved the seeds from their best plants to use the following season. This process of "selective breeding" made crops that were bigger, more productive, tastier, or prettier than their wild ancestors. But because only the individuals with the most useful traits were used to produce the next generation, it also reduced the crops' genetic diversity. As crops were improved and customized to grow in different locations, gene variations that might help them resist a new challenge—say a new disease or pest, drought, or a different habitat—were often lost.

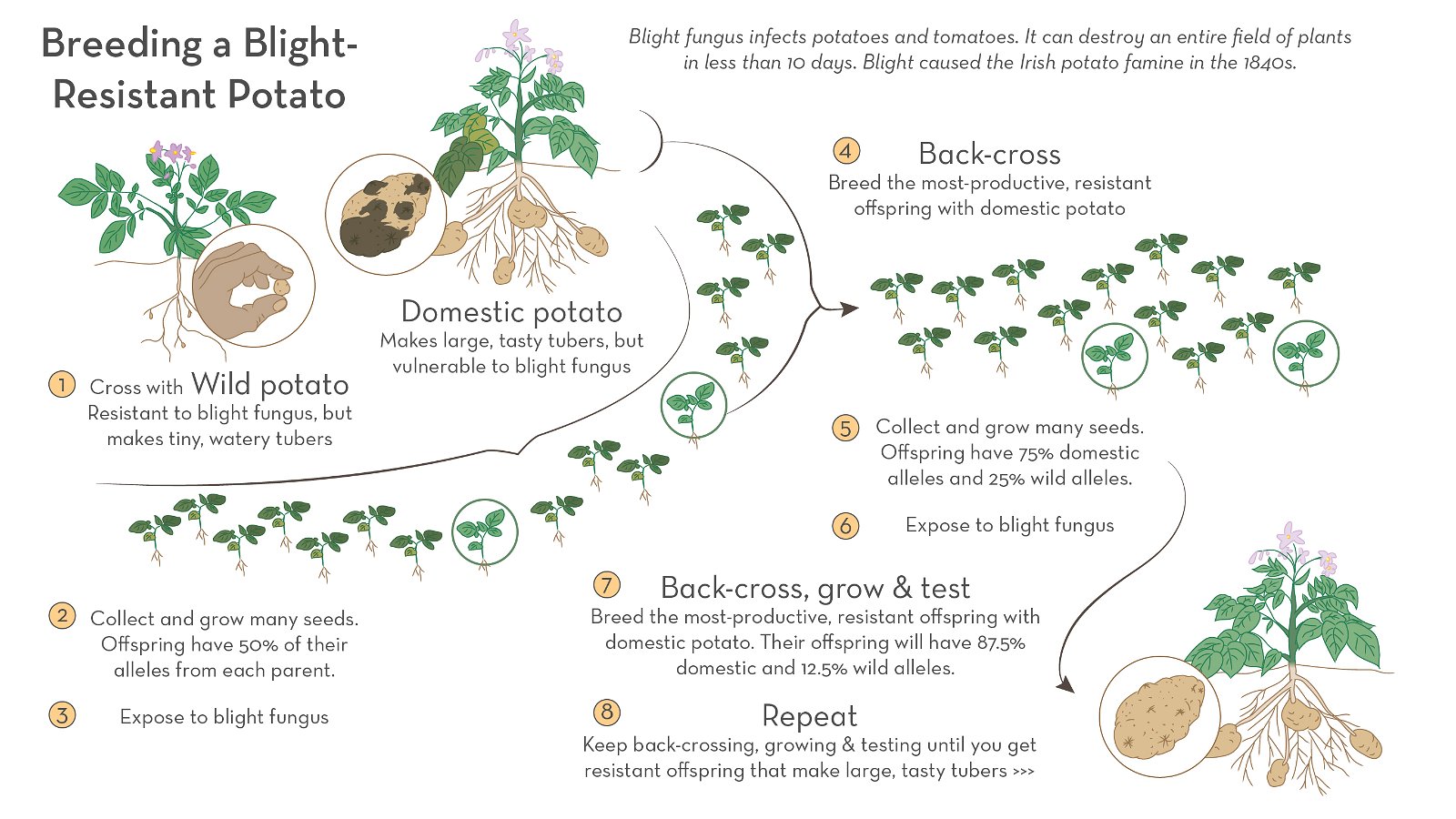

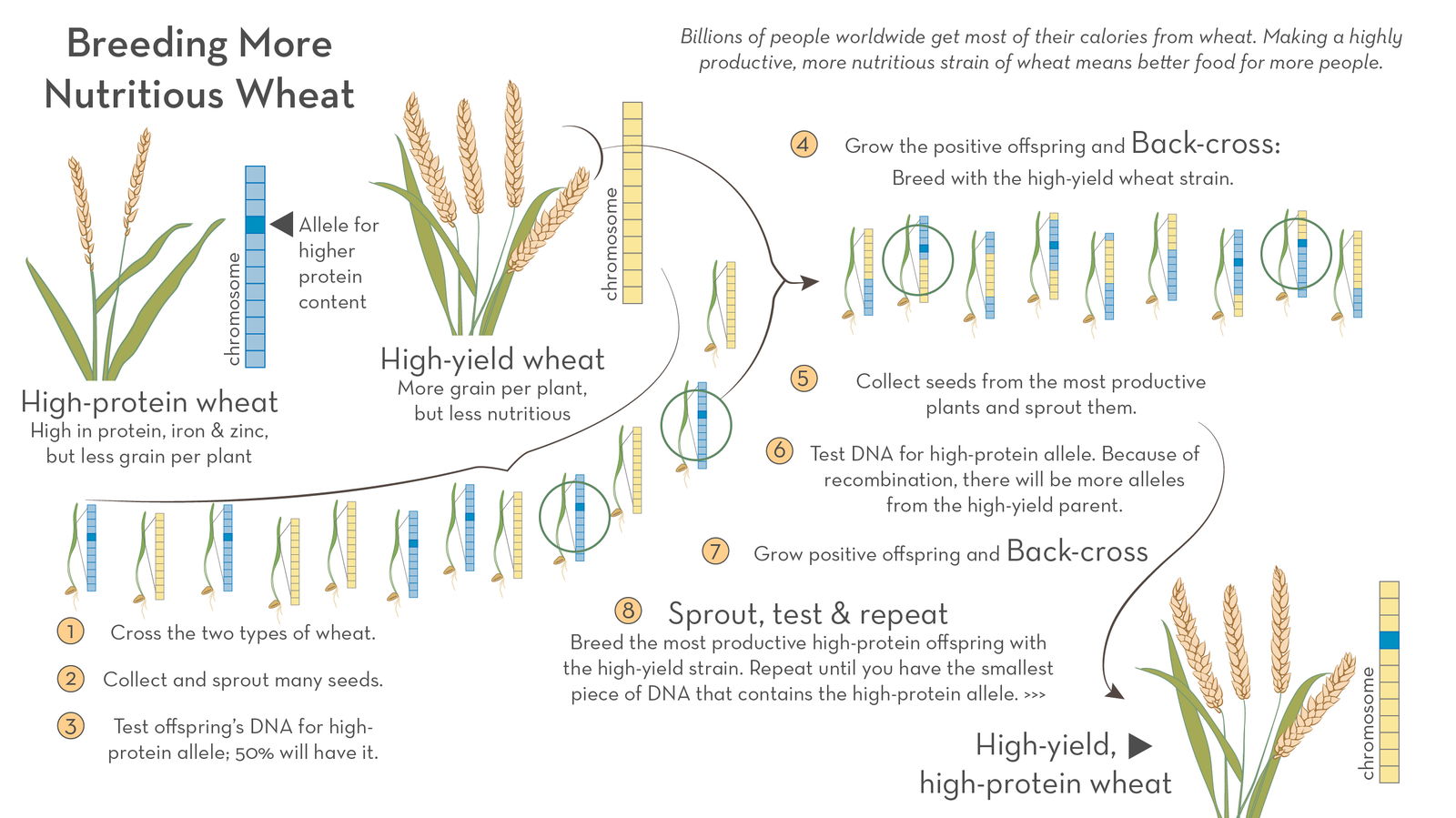

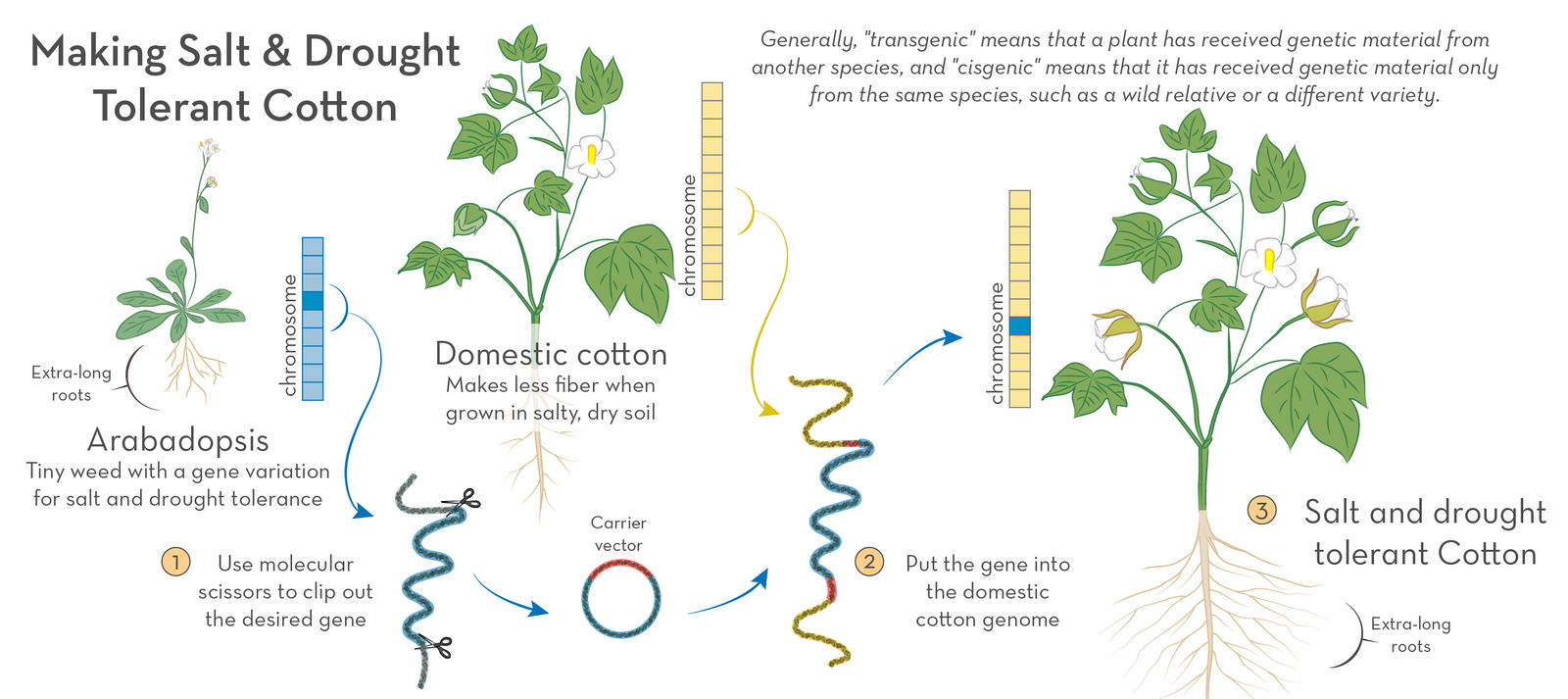

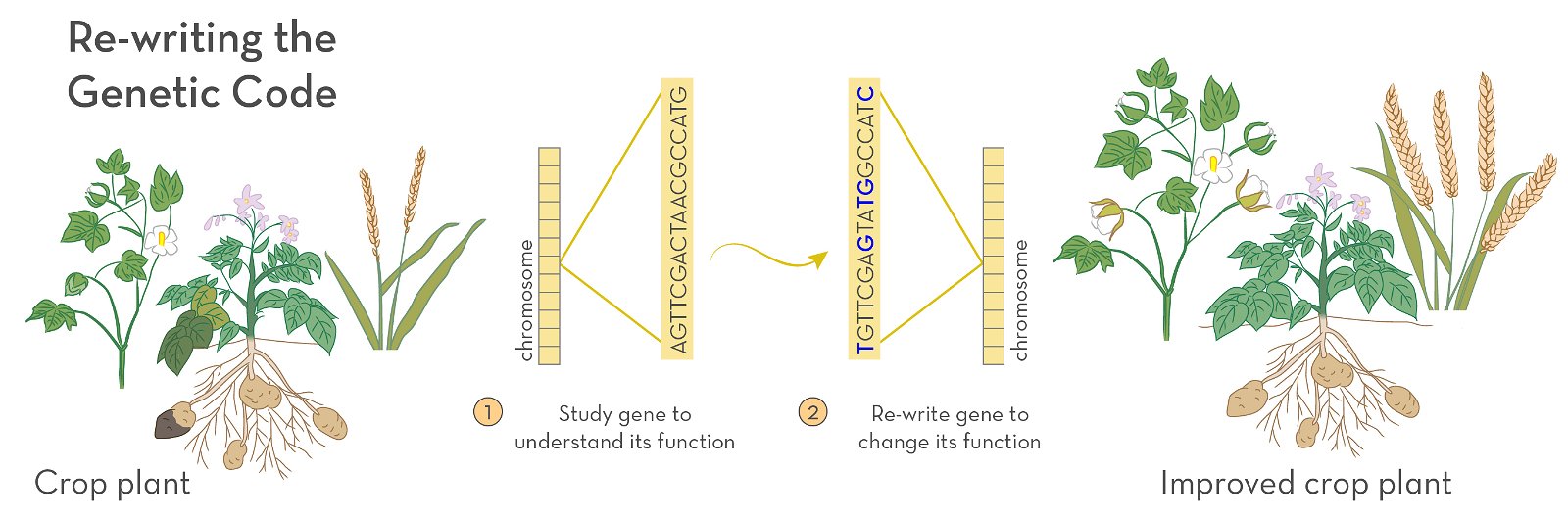

The good news is that helpful genetic variations may still be available in the crop plants' wild cousins, or in less-improved or heirloom varieties. These relatives can be a reservoir of genetic diversity—plant breeders just need to figure out how to get the right genes into the crop plant. Read on to learn how this is done using "traditional" breeding methods and with newer methods that use genomic tools: marker-assisted breeding, transgenic technology, and gene editing.