Cotton comes from a plant

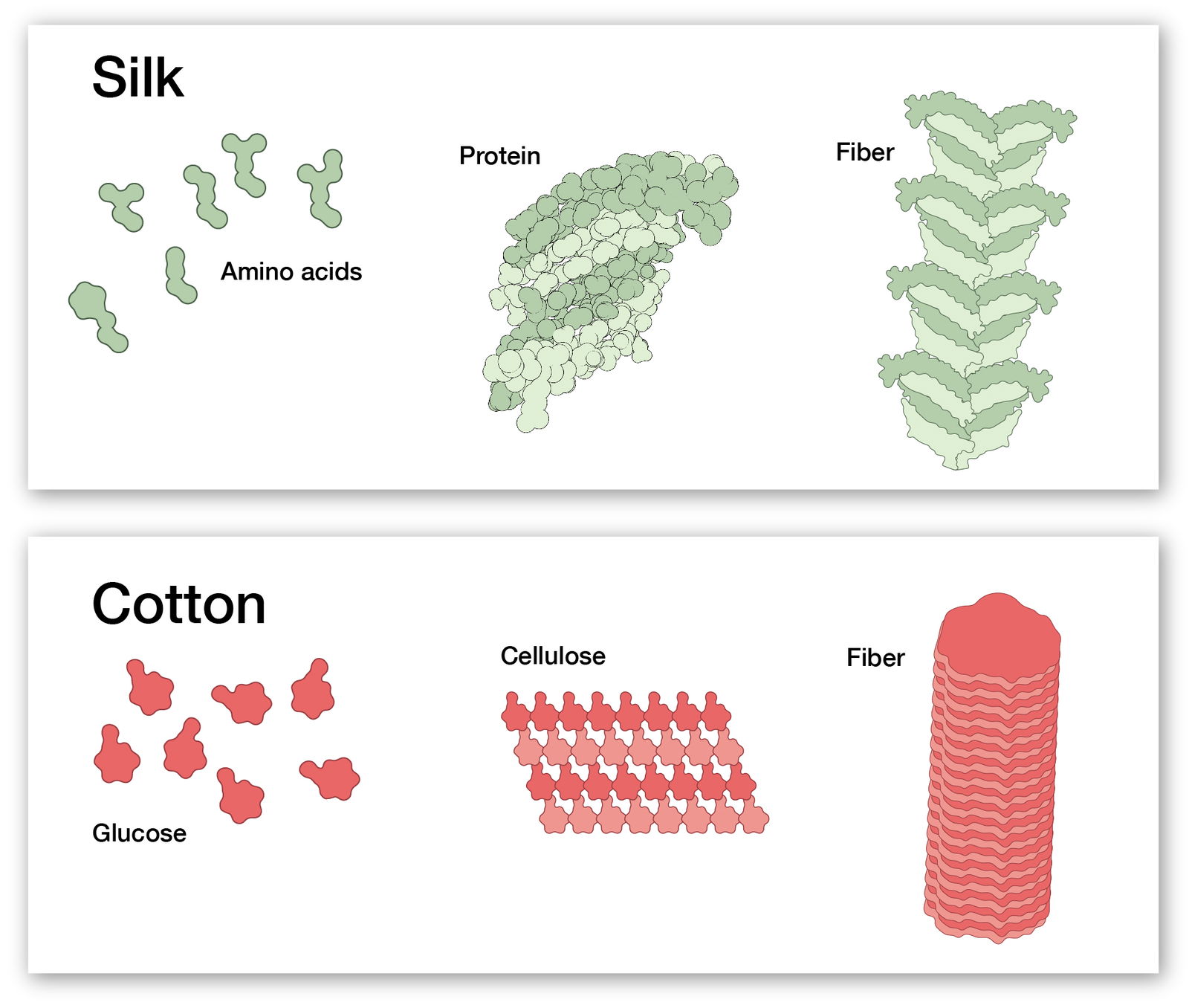

Cotton is the most widely produced natural fiber on the planet. Other natural fibers include silk, made from the cocoons of silkworms; wool, made from the fur of sheep or alpacas; and linen, made from fibers in the stems of flax plants.

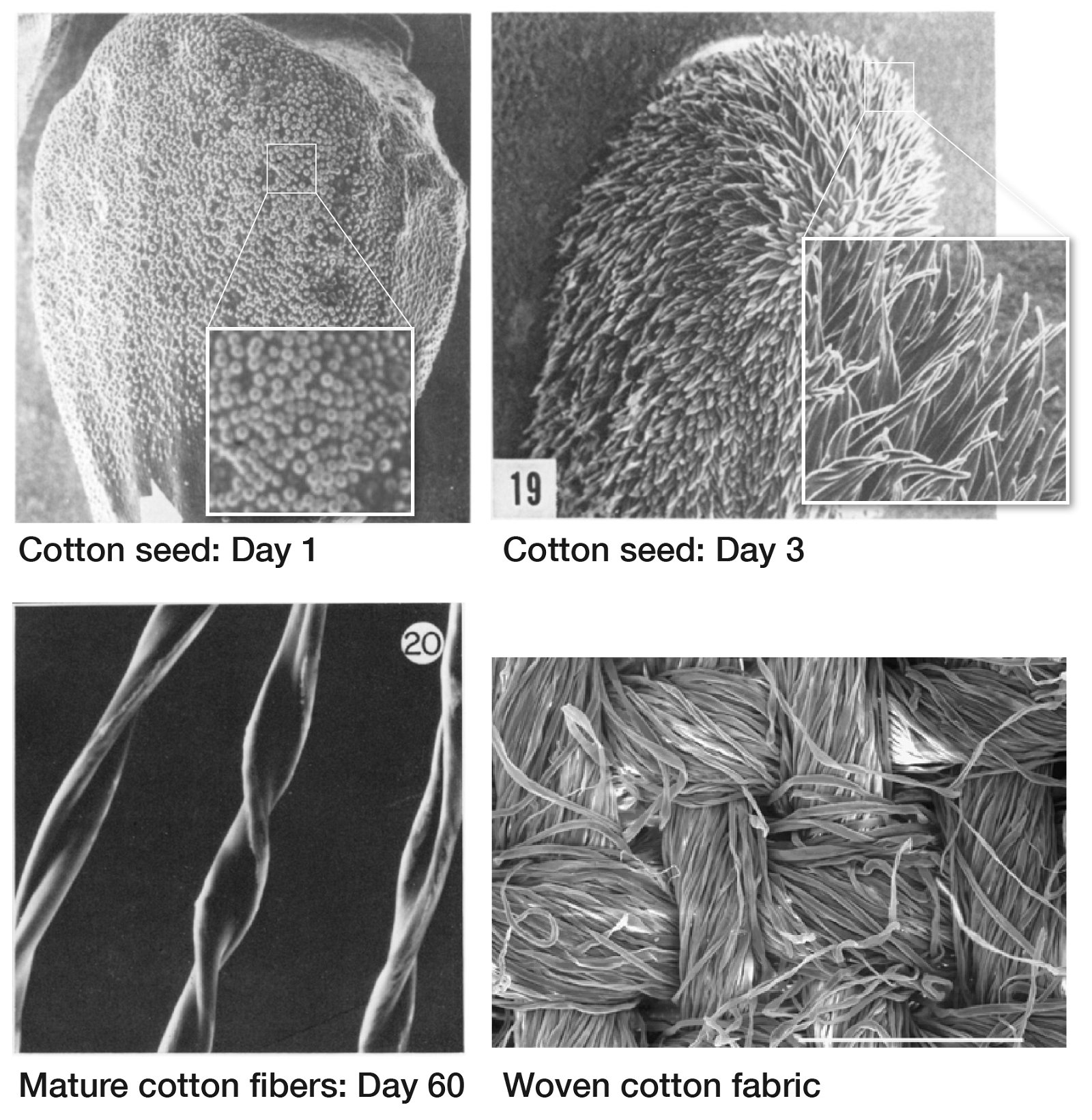

Cotton fibers come from cotton plants. Specifically, they grow from the seed coat—the outer layer of the cotton plant's seeds. Before they can be turned into sheets or t-shirts, the cotton seeds must first be separated from the plant, and then the fibers from the seeds.

Stages of cotton flower and fruit formation: 1. Flower bud; 2. Flower; 3. Developing seed pod; 4. Seed pod dries and opens, revealing mature cotton fibers.