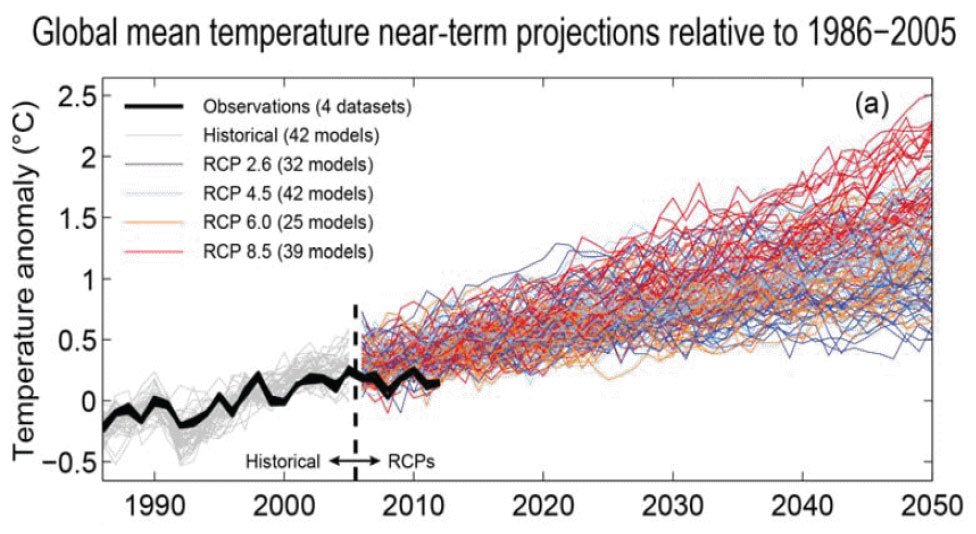

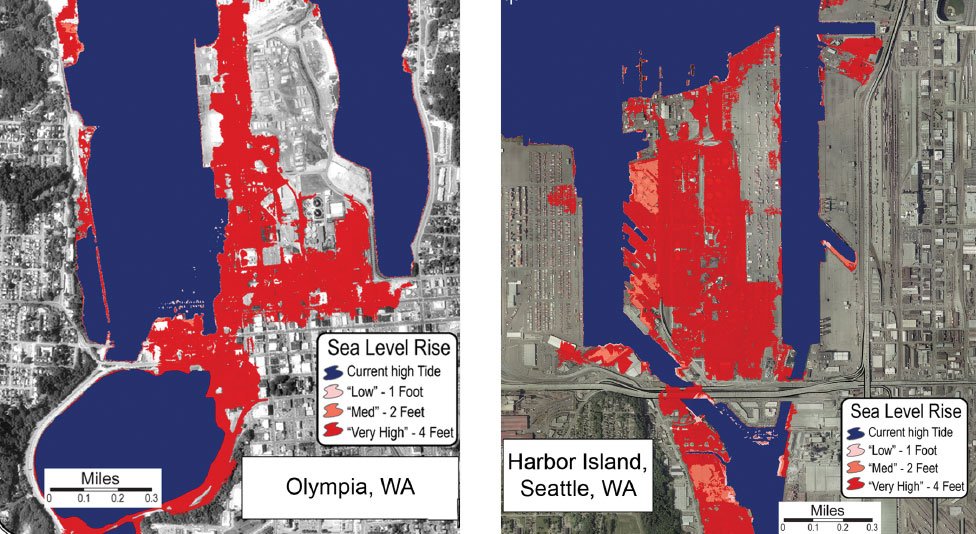

Predictive models forecast what will happen in the future. These models work because natural events often follow patterns.

To calculate the probability of a future outcome, most predictive models factor in historical data along with what we know about rules and relationships among the variables involved.

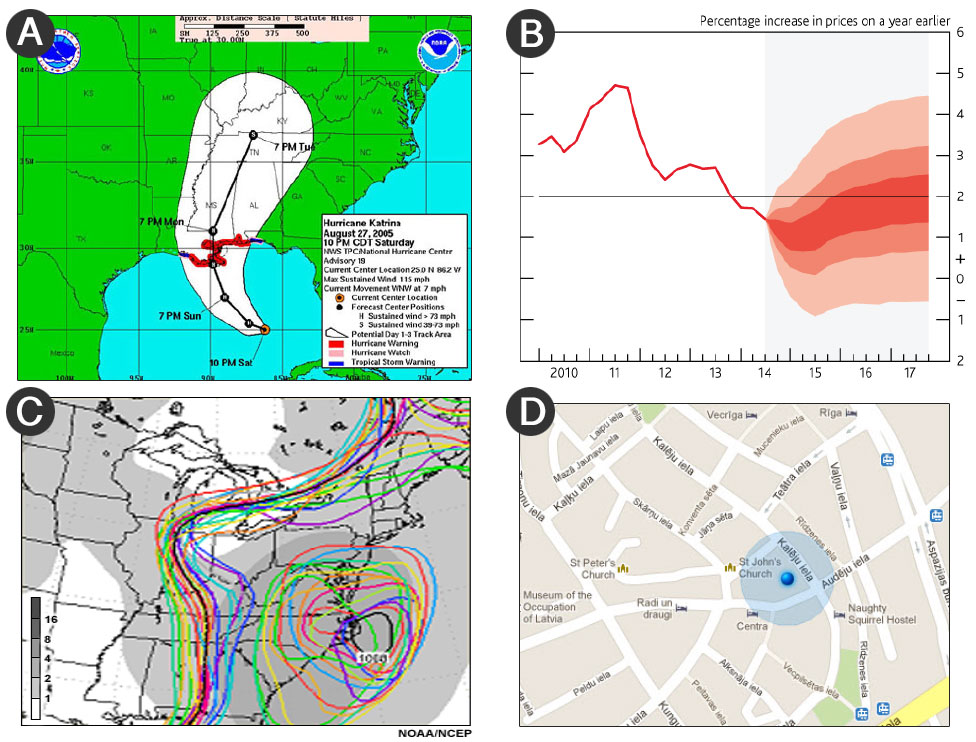

Because they deal with the future, which hasn’t happened yet, all predictive models have a degree of uncertainty. So most predictive models include some way to communicate the nature of that uncertainty.

- Human error in data collection

- Accuracy of measuring equipment

- Precision of data collection device

- Historical conditions no longer apply

- Random behavior of the system itself, no pattern

- Important variables left out of the model

- The predictive model itself influences the outcome

Representing uncertainty in prediction models: (A) The “cone of uncertainty” around the predicted track of a hurricane grows wider as we look further into the future. (B) A “fan chart” of economic inflation showing historical data (solid line) and predicted outcomes. Ranges of possible outcomes are shown as bands of color, with the darker colors representing more likely outcomes. (C) A spaghetti plot showing forecasts for atmospheric pressure. Each colored line represents a different forecast model prediction. The greater the distance between the lines, the greater the uncertainty. (D) The wider blue circle shows uncertainty about geographic location, which usually stems from limitations of the measuring device. As the device collects more location data, the circle may grow smaller.