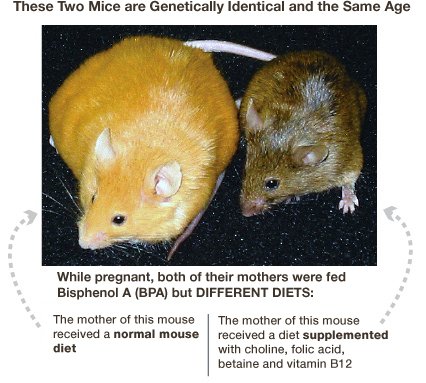

Unlike behavior or stress, diet is one of the more easily studied, and therefore better understood, environmental factors in epigenetic change.

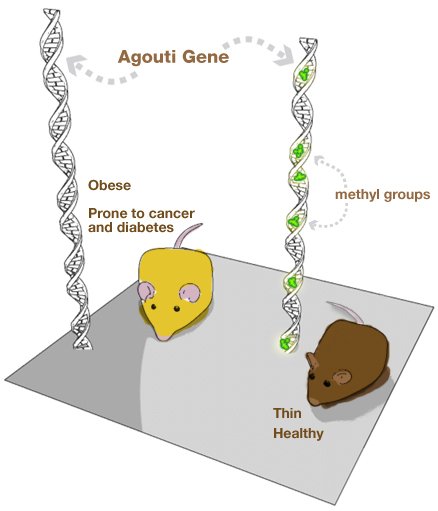

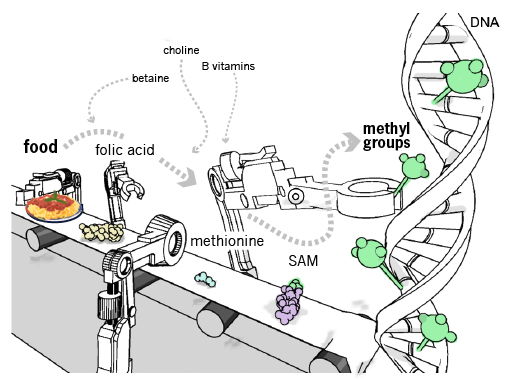

The nutrients we extract from food enter metabolic pathways where they are manipulated, modified, and molded into molecules the body can use. One such pathway is responsible for making methyl groups - important epigenetic tags that silence genes.

Familiar nutrients like folic acid, B vitamins, and SAM-e (S-Adenosyl methionine, a popular over-the-counter supplement) are key components of this methyl-making pathway. Diets high in these methyl-donating nutrients can rapidly alter gene expression, especially during early development when the epigenome is first being established.

Take a detailed look at the nutrients that affect our epigenome and the foods they come from.

Nutrients from our food are funneled into a biochemical pathway that extracts methyl groups and then attaches them to our DNA.