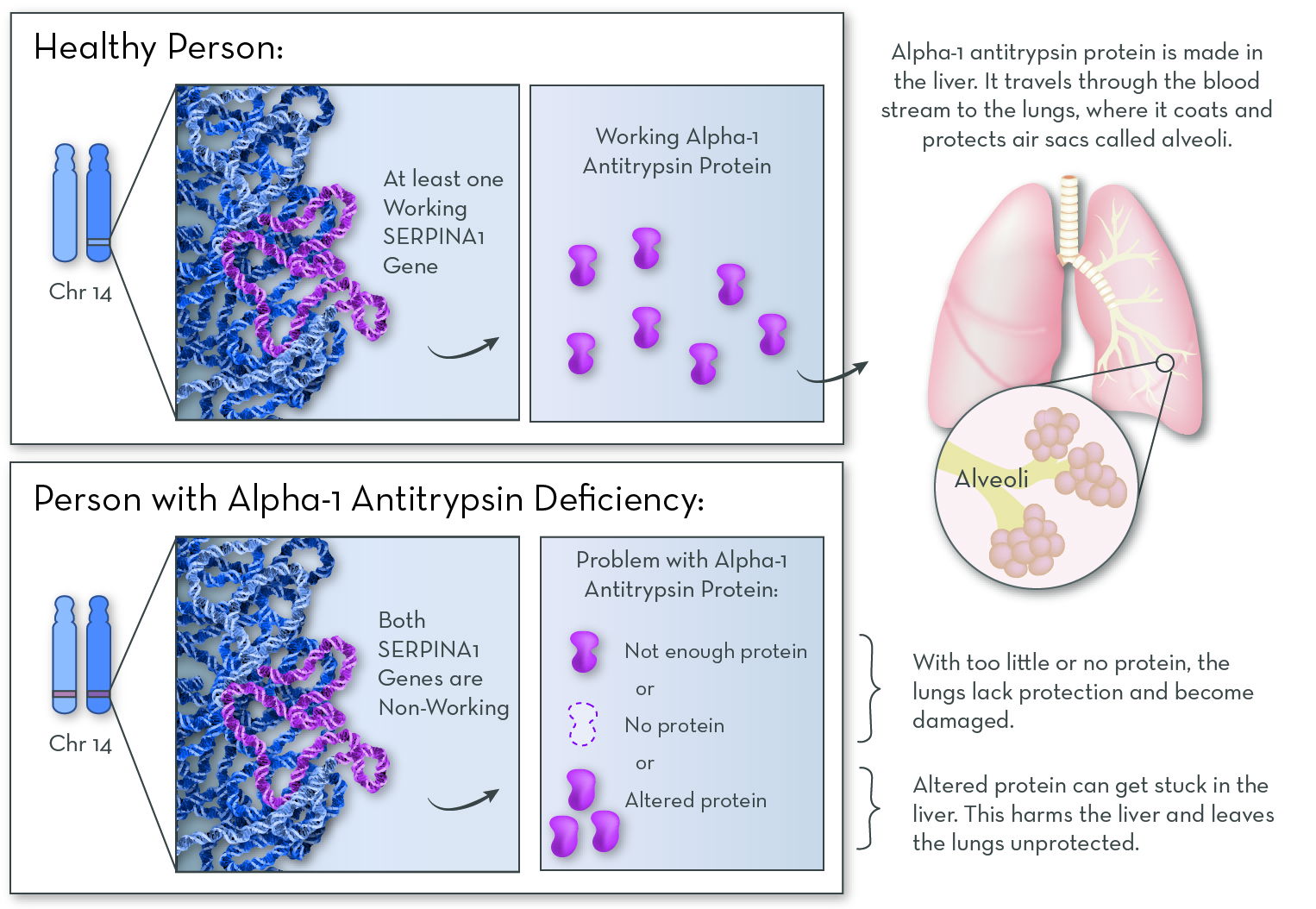

What is Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (Alpha-1)?

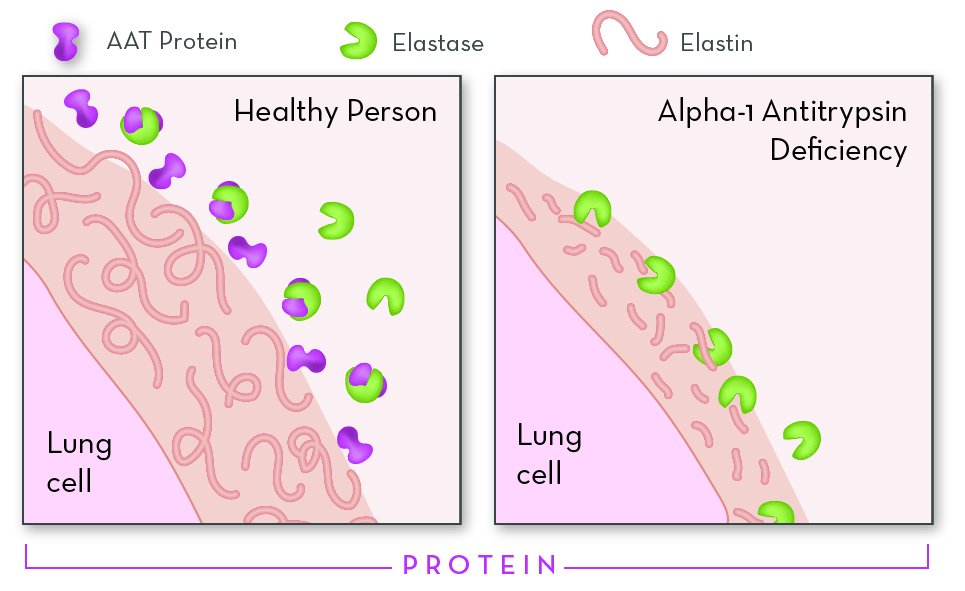

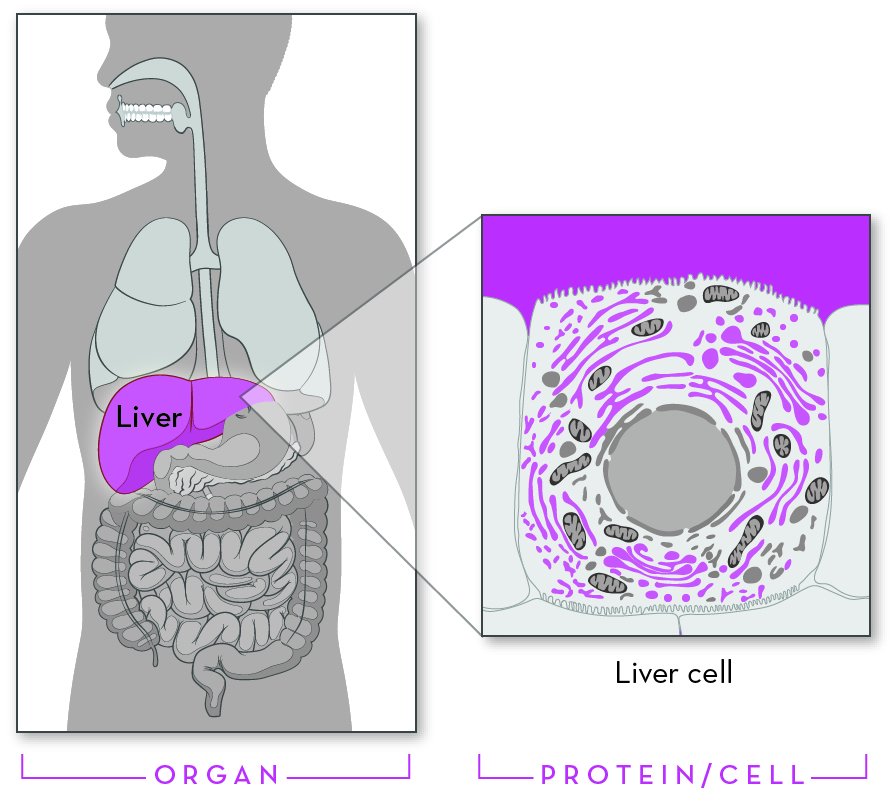

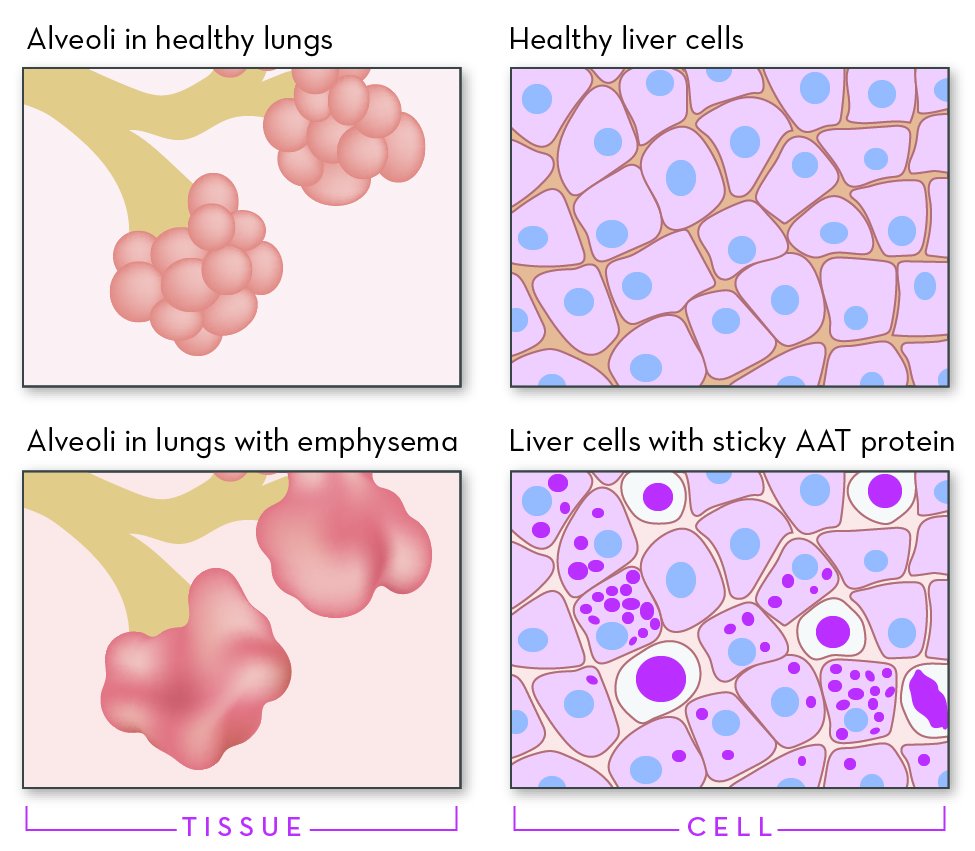

Alpha-1 is a genetic disorder that affects the lungs and sometimes the liver. Even though it is one of the most common genetic disorders, Alpha-1 can be hard to diagnose. One challenge is that most people with Alpha-1 are healthy for at least the first few decades of their lives. For many, symptoms do not appear until middle adulthood. Another challenge is that the effects of the disorder look a lot like other conditions. Lung symptoms can mimic asthma, bronchitis, or smoking-induced emphysema. Liver symptoms can mimic cirrhosis. This often leads to misdiagnosis and a delay in treatment. In the United States, more than 90% of people with Alpha-1 never learn that they have it.