What is Cystic Fibrosis?

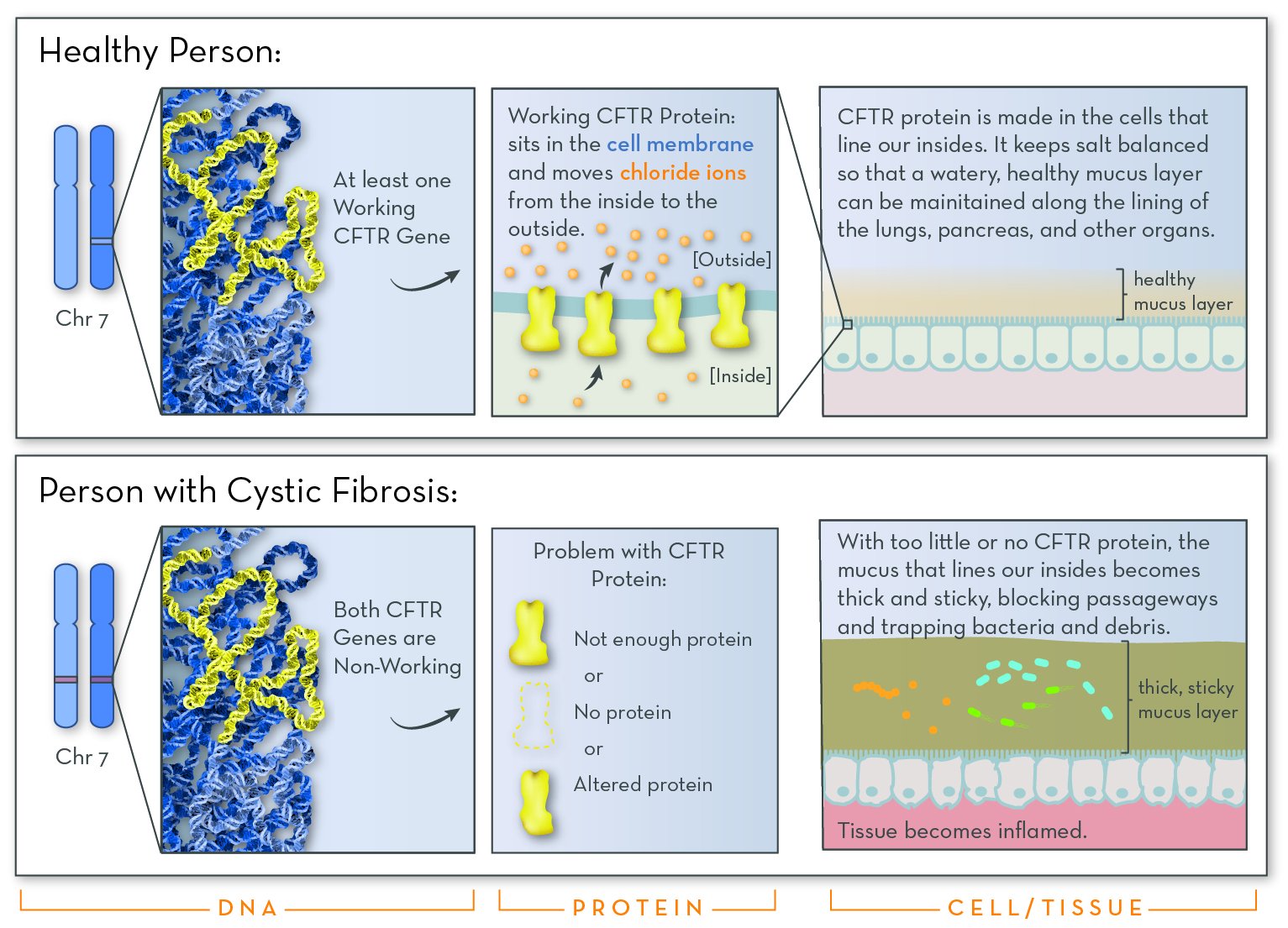

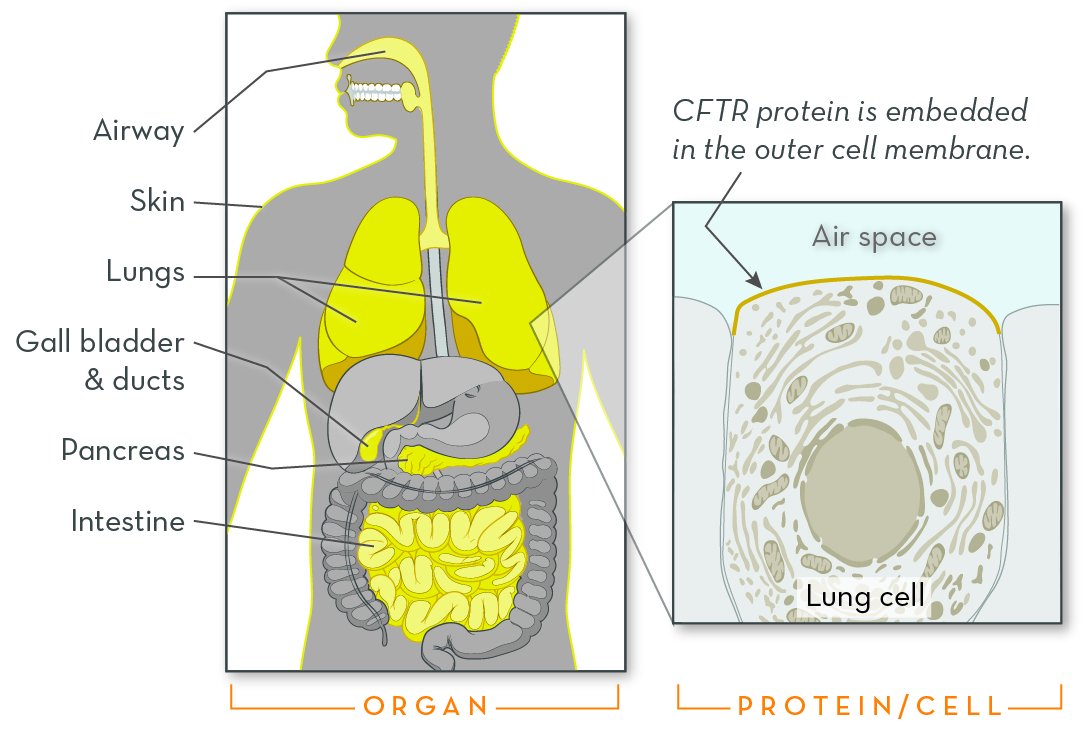

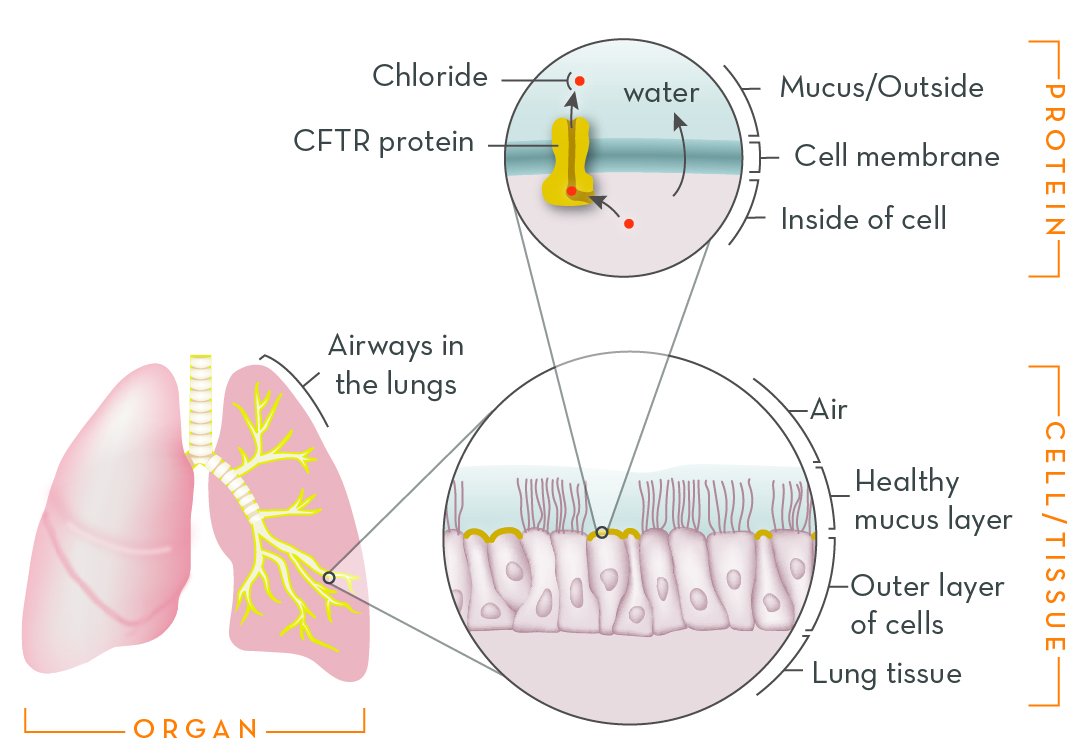

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder that alters salt and water balance in the body. It affects multiple organs, especially the lungs and digestive system.

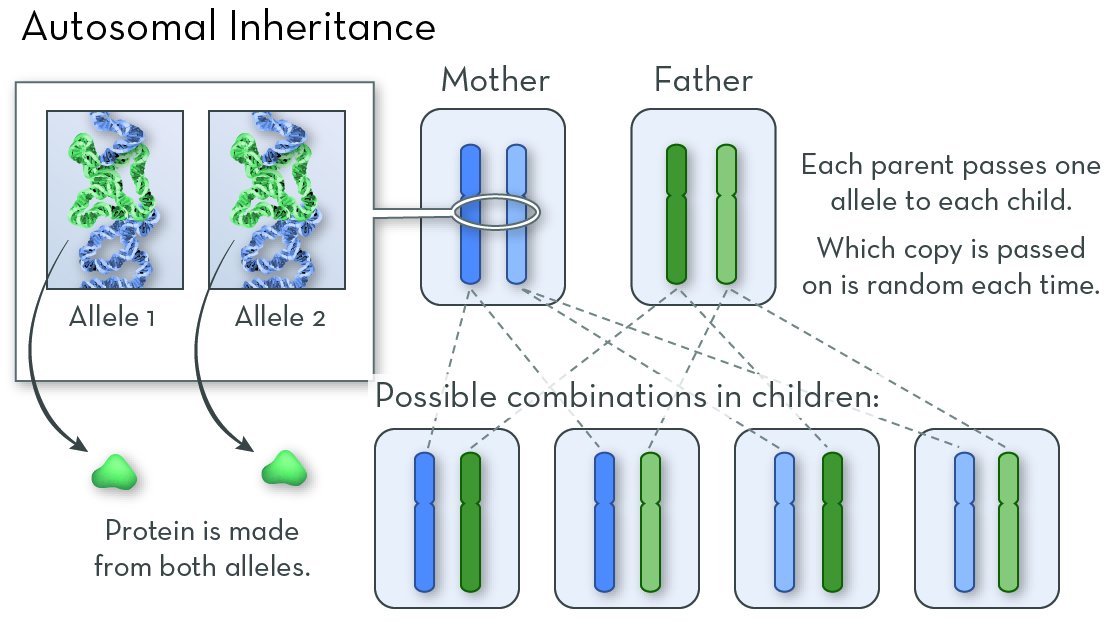

More than 10 million people in the US carry a cystic fibrosis-causing gene variation, but most do not know it. Early diagnosis leads to better outcomes, so cystic fibrosis is tested for in most newborn genetic screening panels. Starting treatment right away can prevent lung damage and improve nutrition, leading to a much longer and healthier life.