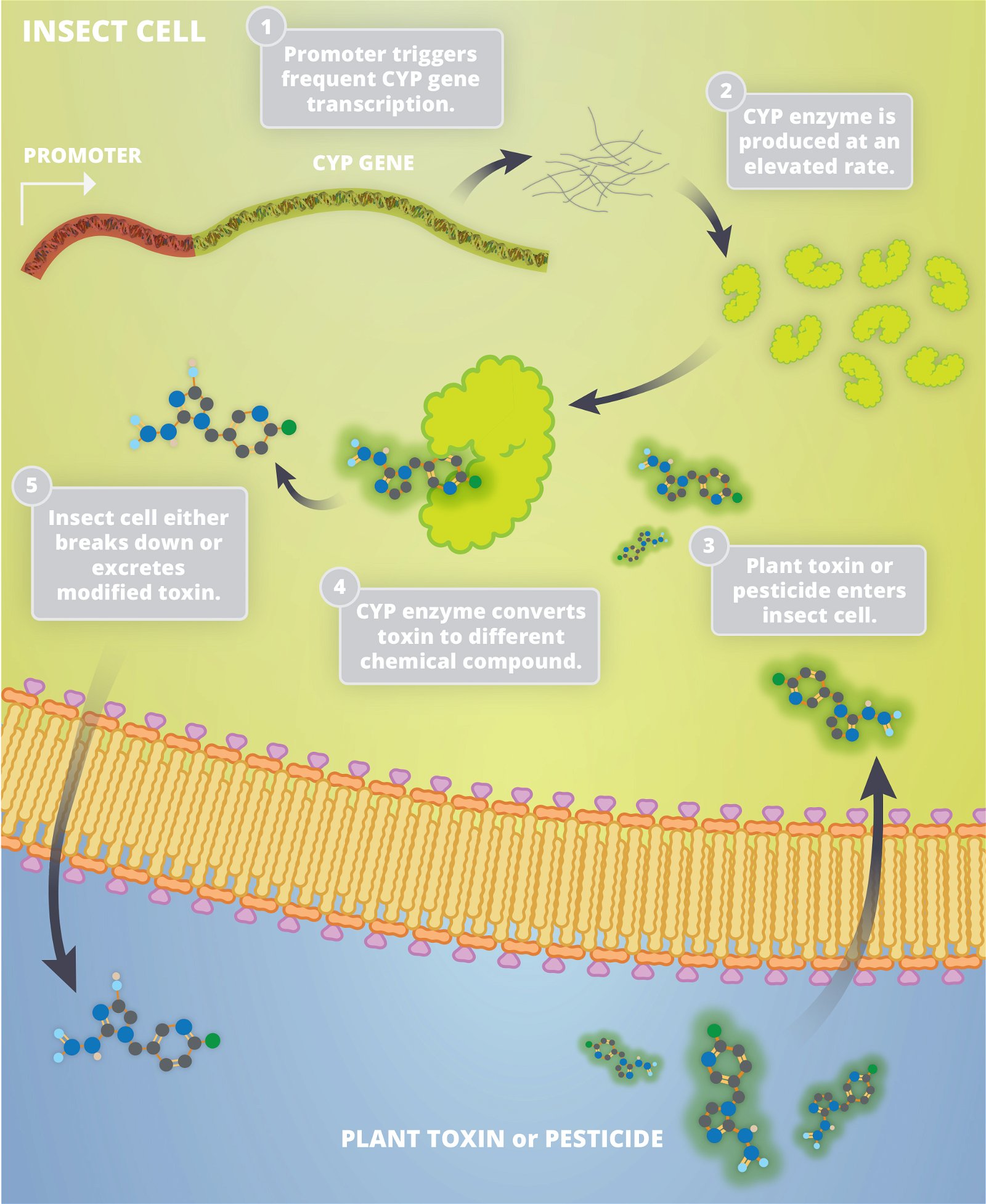

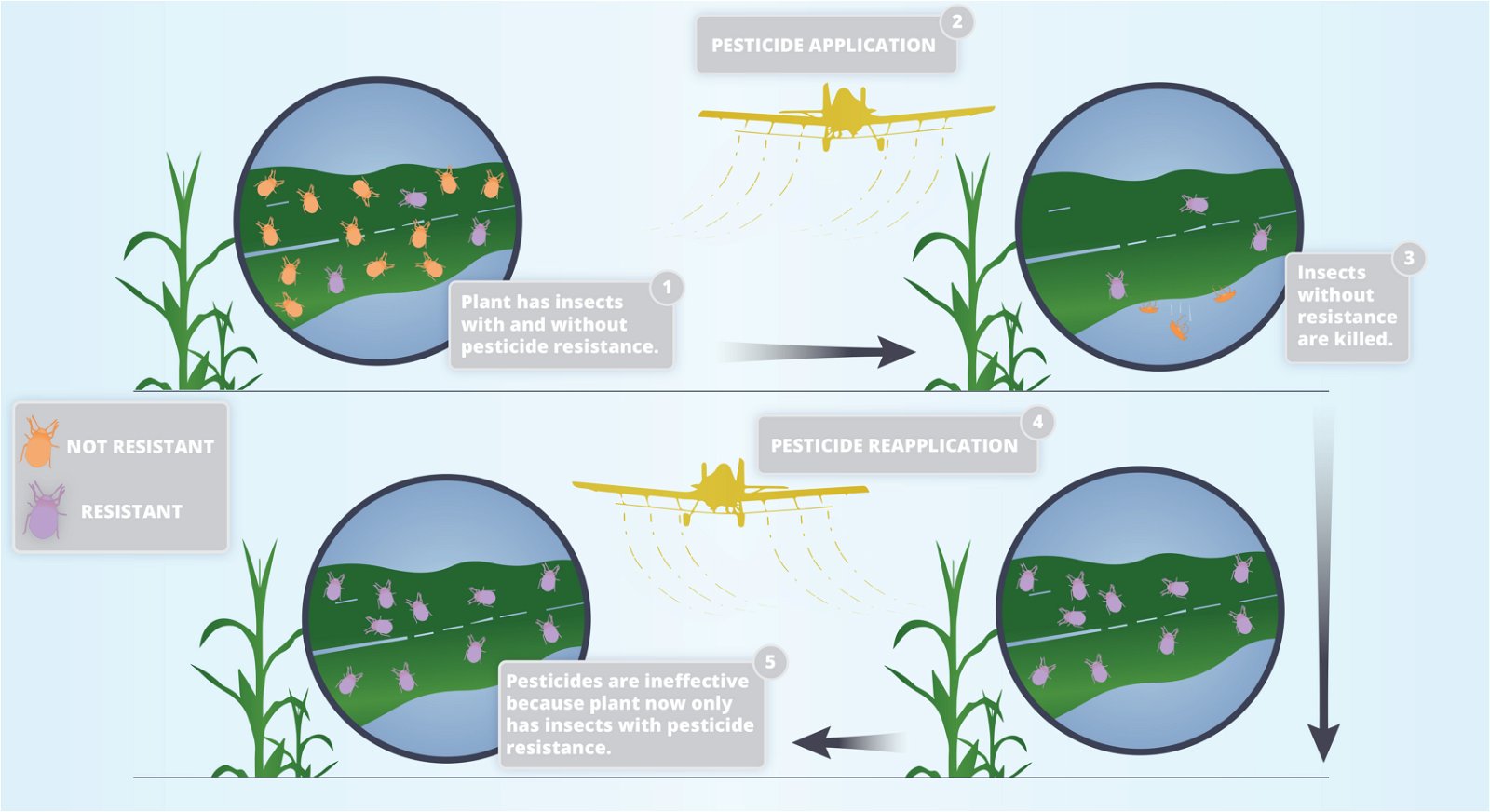

Plants produce a staggering array of diverse chemical compounds. Many of these natural compounds deter or kill herbivores, just like the pesticides that humans make. Yet, some insect herbivores have evolved ways to overcome these toxic compounds.

Related content

For a refresher on traits, DNA, genes, and more visit our Basic Genetics page

This tobacco hornworm caterpillar is eating a tobacco leaf. Tobacco plants make a toxin called nicotine. These specialist herbivores can eat tobacco without harmful effects because they make an enzyme that can detoxify nicotine. Amazingly, they also emit some of the nicotine they’ve eaten from holes in their sides to ward off predators like spiders.