The discovery that antibiotics can treat bacterial infections dramatically changed human health, and many once deadly infections are now curable. Yet often we hear about bacteria that are no longer killed effectively by antibiotics. These bacteria are known as antibiotic resistant, and they’re a growing problem in medicine.

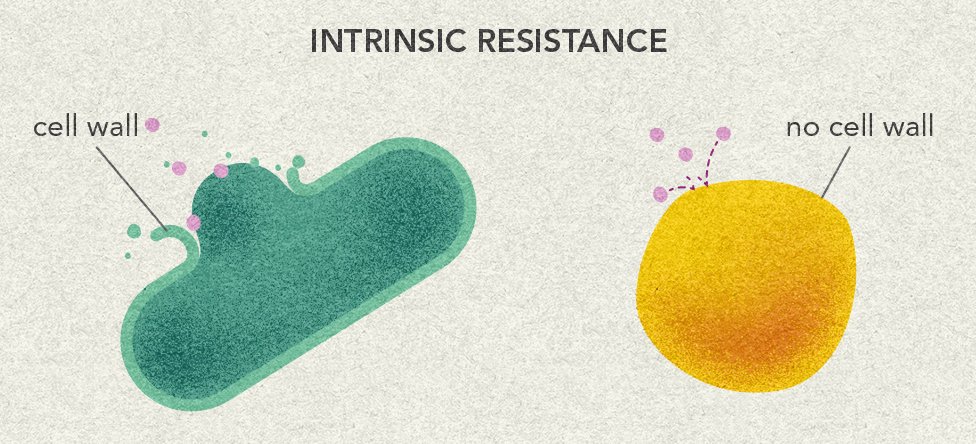

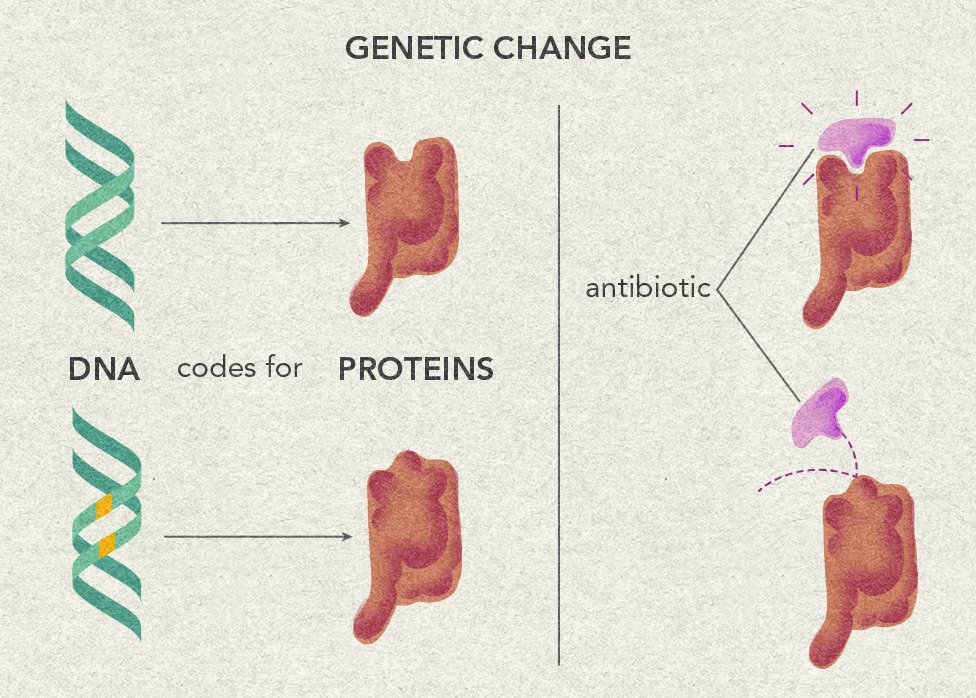

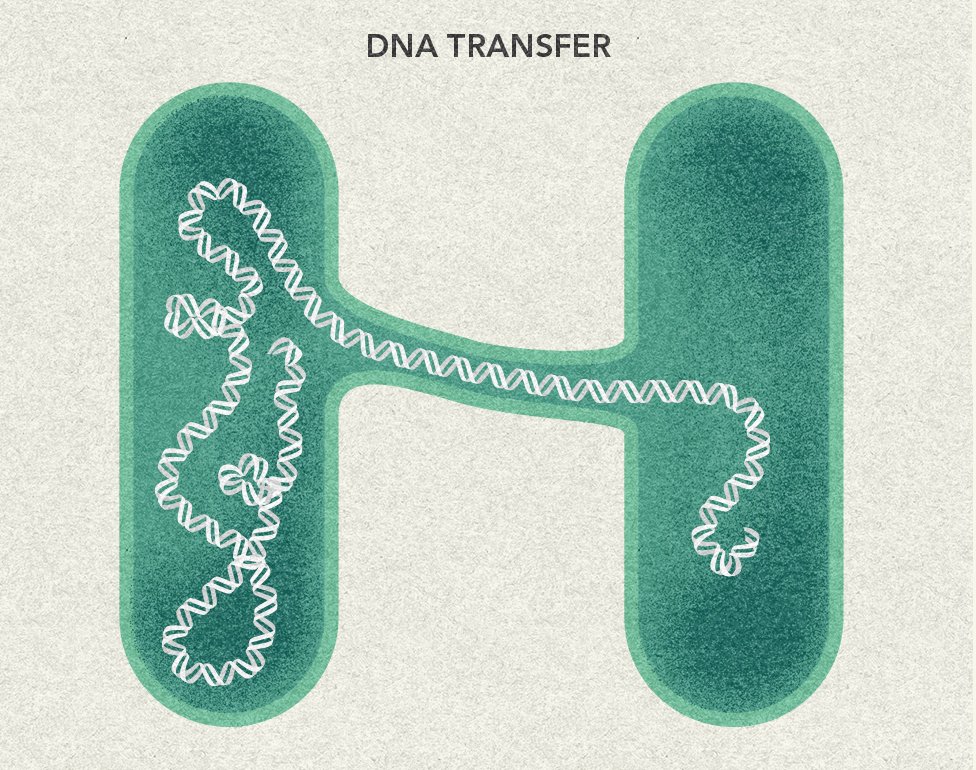

Frequent antibiotic use over long periods of time puts selective pressure on bacteria, and causes resistance to spread. When an antibiotic is used to treat a typical bacterial infection, most bacteria are killed. Sometimes, however, a bacterium with an advantage lives. This bacterium can then reproduce and pass its advantage on, creating many more antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Antibiotic resistance is not new. In fact, it existed long before people discovered how to use antibiotics as medicine. Many antibiotics are made from compounds bacteria or fungi produce to help them compete in their natural environments. This means that in nature, bacteria are under selective pressure to pass on advantages, just like they are when we treat an infection with antibiotics. Sometimes in medicine, antibiotics are used too often or incorrectly, which can cause resistance to spread faster than it would naturally.