Sex linkage applies to genes that are located on the sex chromosomes. These genes are considered sex-linked because their expression and inheritance patterns differ between males and females. While sex linkage is not the same as genetic linkage, sex-linked genes can be genetically linked (see bottom of page).

Sex Linkage

Sex Chromosomes

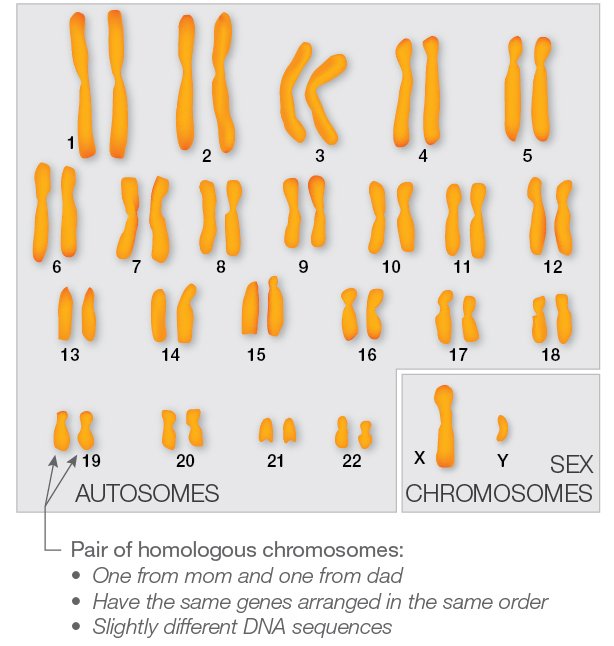

Sex chromosomes determine whether an individual is male or female. In humans and other mammals, the sex chromosomes are X and Y. Females have two X chromosomes, and males have an X and a Y.

Non-sex chromosomes are also called autosomes. Autosomes come in pairs of homologous chromosomes. Homologous chromosomes have the same genes arranged in the same order. So for all of the genes on the autosomes, both males and females have two copies.

A female’s two X chromosomes also have the same genes arranged in the same order. So females have two copies of every gene, including the genes on sex chromosomes.

The X and Y chromosomes, however, have different genes. So for the genes on the sex chromosomes, males have just one copy. The Y chromosome has few genes, but the X chromosome has more than 1,000. Well-known examples in people include genes that control color blindness and male pattern baldness. These are sex-linked traits.

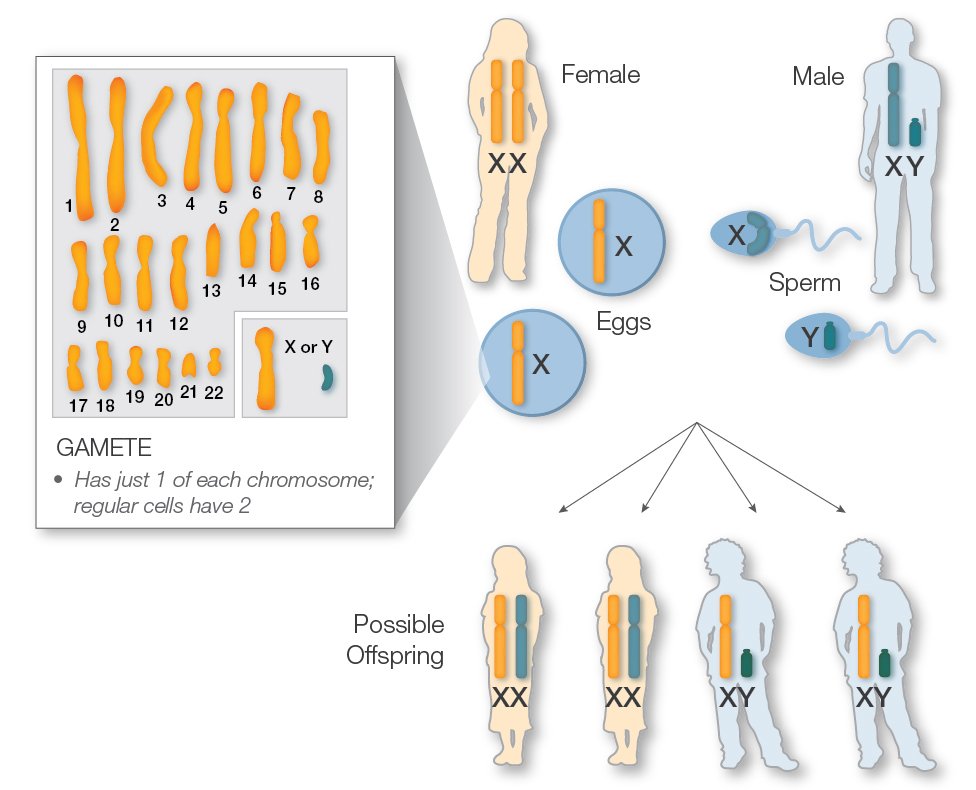

Inheritence of Sex Chromosomes in Mammals

Meiosis is the process of making gametes, also known as eggs and sperm in most animals. During meiosis, the number of chromosomes is reduced by half, so that each gamete gets just one of each autosome and one sex chromosome.

Female mammals make eggs, which always have an X chromosome. And males make sperm, which can have an X or a Y.

Egg and sperm join to make a zygote, which develops into a new offspring. An egg plus an X-containing sperm will make a female offspring, and an egg plus a Y-containing sperm will make a male offspring.

- Female offspring get an X chromsome from each parent

- Males get an X from their mother and a Y from their father

- X chromosomes never pass from father to son

- Y chromosomes always pass from father to son

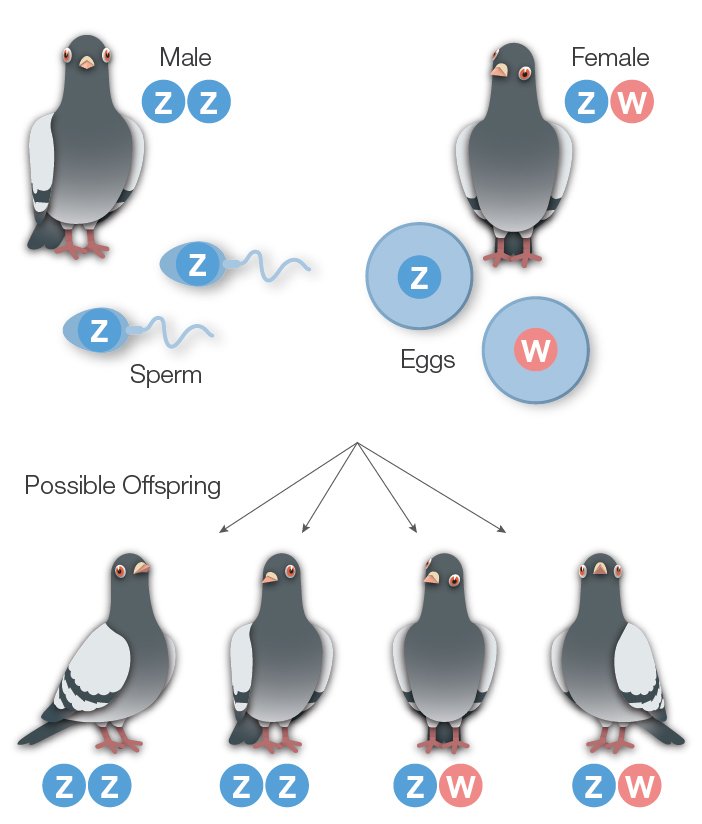

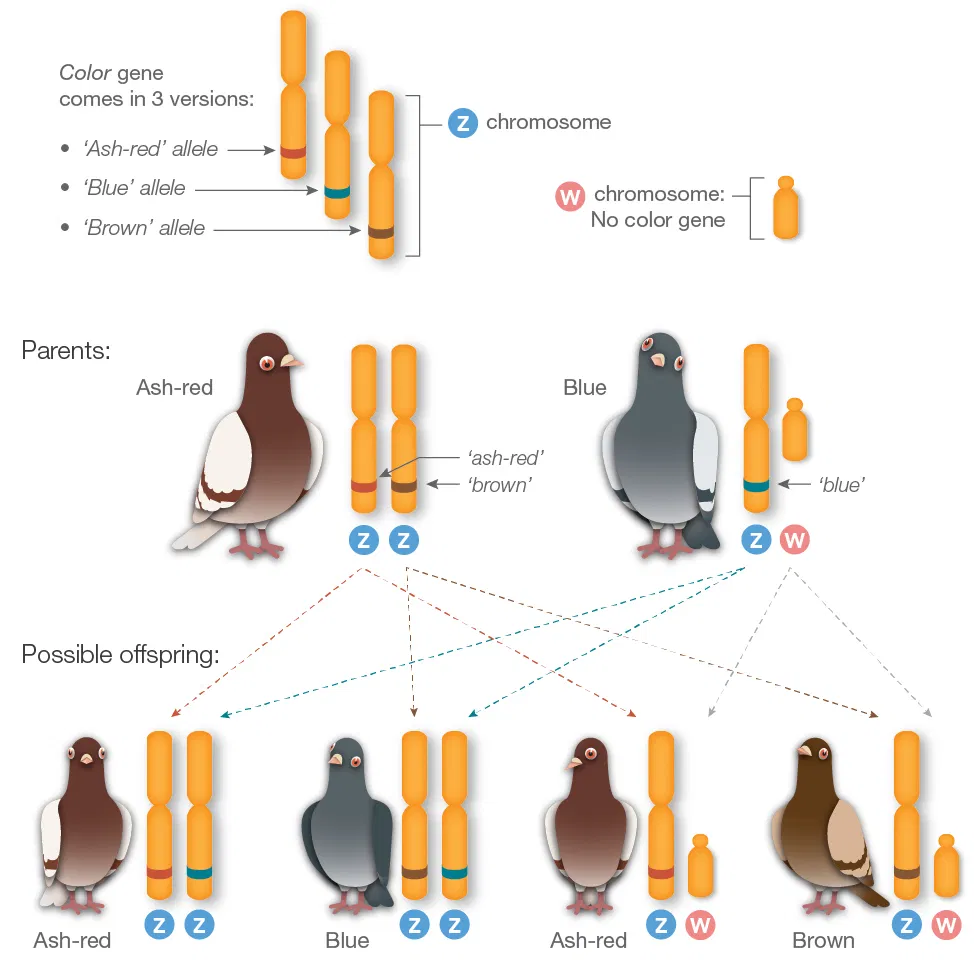

Sex Chromosomes in Pigeons

The way sex determination works in birds is nearly the reverse of how it works in mammals. If you’ve played Pigeonetics, you know that the sex chromosomes in birds are Z and W. Male birds have two Z chromosomes, and females have a Z and a W. Male birds make sperm, which always have a Z chromosome. Female gametes (eggs) can have a Z or a W.

- Male offspring get a Z chromsome from each parent

- Females get a Z from their father and a W from their mother

- Z chromosomes never pass from mother to daughter

- W chromosomes always pass from mother to daughter

In birds, it’s the males that have two copies of every gene, while the females have just one copy of the genes on the sex chromosomes. The W-chromosome is small with few genes. But the Z-chromosome has many sex-linked genes, including genes that control feather color and color intensity.

Inheritance of Sex-Linked Genes

For genes on autosomes, we all have two copies—one from each parent. The two copies may be the same, or they may be different. Different versions of the same gene are called “alleles” (uh-LEELZ). Genes code for proteins, and proteins make traits.* Importantly, it’s the two alleles working together that affect what we see—also called a “phenotype.”

Female pigeons (ZW) have just one Z chromosome, and therefore just one allele for each of the genes located there. One gene on the Z chromosome affects feather color; three different alleles make feathers blue, ash-red, or brown. In a female bird (ZW), her single color allele determines her feather color. But in males (ZZ), two alleles work together to determine feather color according to their dominance. That is, 'ash-red' is dominant to 'blue', which is dominant to 'brown'.

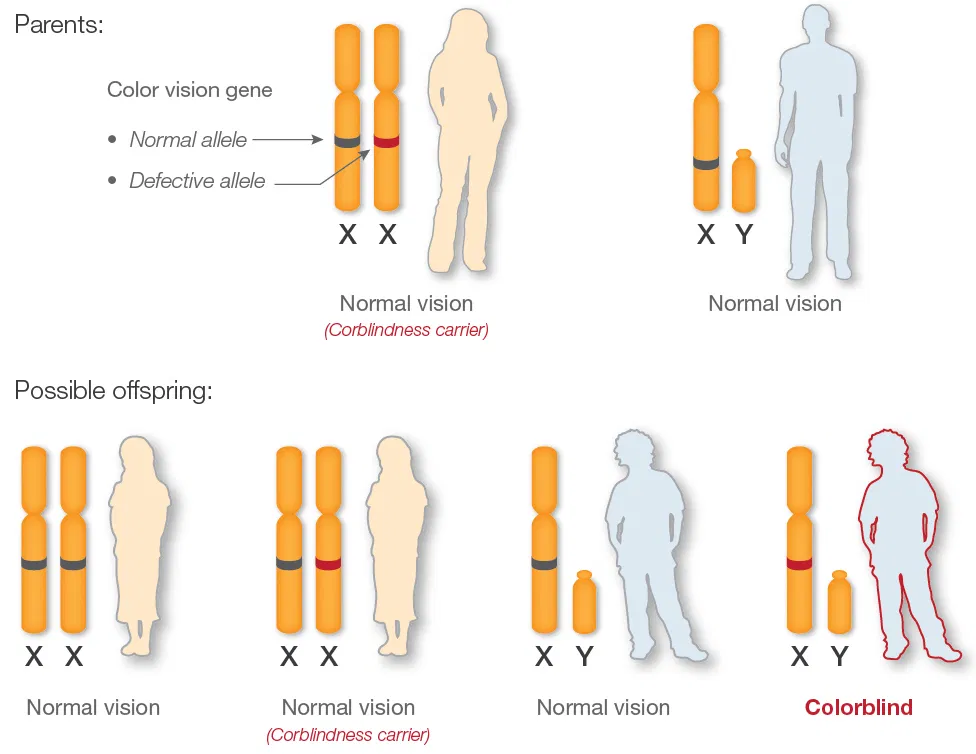

Having two copies of a gene can be important when one copy is “broken” or defective. A functional second copy can often work well enough on its own, acting as a sort of back-up to prevent problems. With sex-linked genes, male mammals (and female birds) have no back-up copy. In people, a number of genetic disorders are sex-linked, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy and hemophilia. These and other sex-inked disorders are much more common in boys than in girls.

Red/green colorblindness is also caused by a defective gene on the X-chromosome. You need at least one working copy of the gene to be able to see red and green. Since boys have just one X-chromosome, which they receive from their mother, inheriting one defective copy of the gene will render them colorblind. Girls have two X-chromosomes; to be colorblind they must inherit two defective copies, one from each parent. Consequently, red-green colorblindness is much more frequent in boys (1 in 12) than in girls (1 in 250).

*Some genes code for functional RNAs, which also influence our traits.

Recombination and Sex-Linked Genes

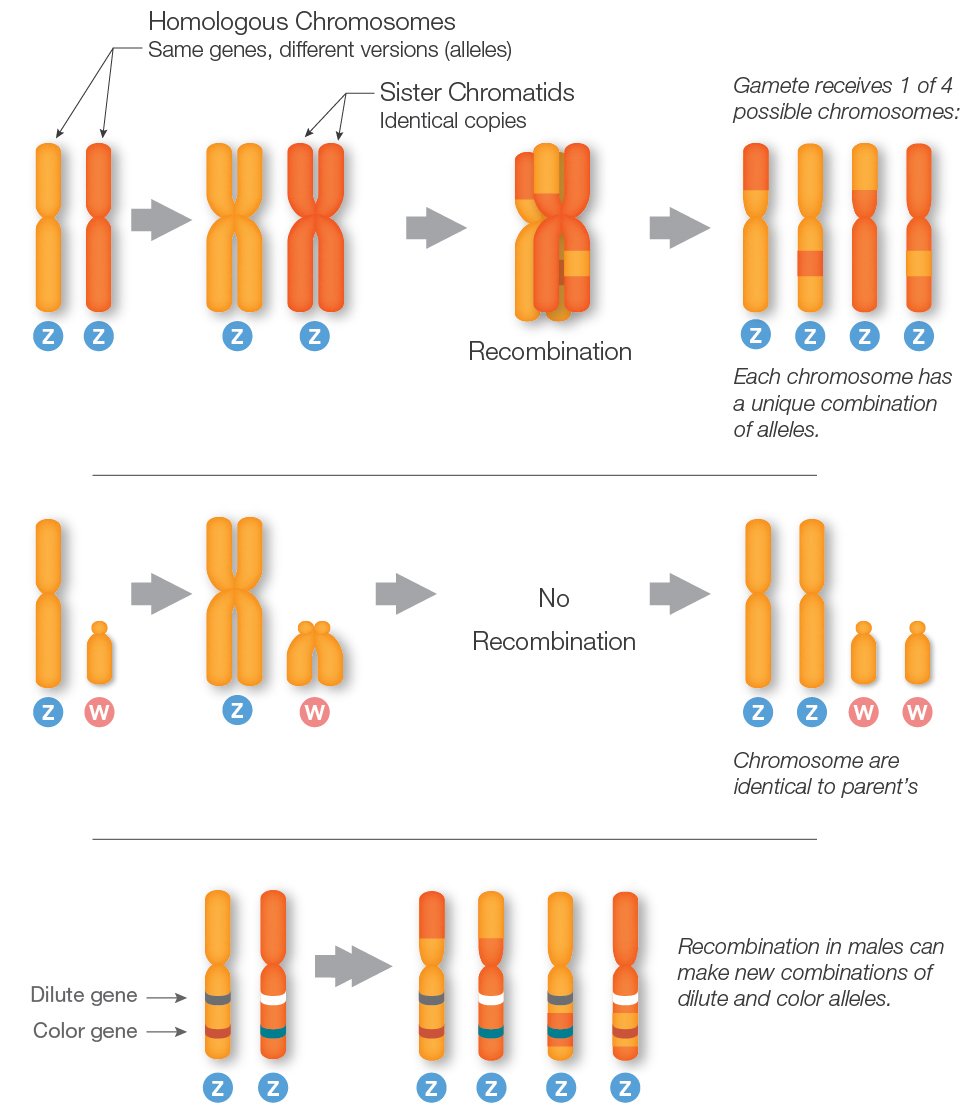

When gametes (egg and sperm) form, chromosomes go through a process called recombination. During recombination, homologous chromosomes pair up and exchange stretches of DNA. Recombination makes new allele combinations, which can then be passed to offspring.

When sex chromosomes don’t have a homologue (XY male mammals and ZW female birds, for instance), the sex chromosomes do not recombine.* Instead, the sex chromosomes pass unchanged from parent to offspring. But when sex chromosomes do have a homologue (as in XX female mammals and ZZ male birds), the sex chromosomes recombine to make new allele combinations.

In pigeons, color and dilute (color intensity) are controlled by two genes on the Z chromosome. In males, recombination between homologous Z chromosomes can make new combinations of color and dilute alleles (by chance, some offspring will still receive the same allele combination as the father). But in females, where the Z chromosome does not recombine, the two alleles always pass to offspring together.

* This isn’t entirely true. Portions of the X and Y chromosomes, called the “pseudoautosomal regions,” do pair up and recombine. These regions have the same genes, which are not considered sex-linked even though they’re on the sex chromosomes.

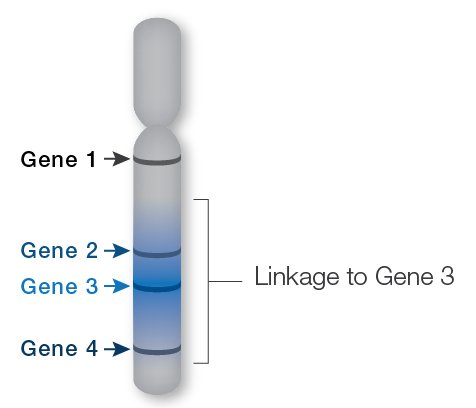

Sex-Linked Genes Can Also Be Genetically Linked

In pigeons, the color and dilute genes are not only sex-linked, they are also genetically linked.

Unlinked genes, whether on the same or different chromosomes, are inherited separately 50% of the time. Genes that are genetically linked are inherited separately less than 50% of the time. The closer together the linked genes are, the less likely it is that a recombination event will happen between them. Color and dilute are separated by recombination about 40% of the time (in males only, of course), so they are not very close together.