What is sound, and why can we hear it?

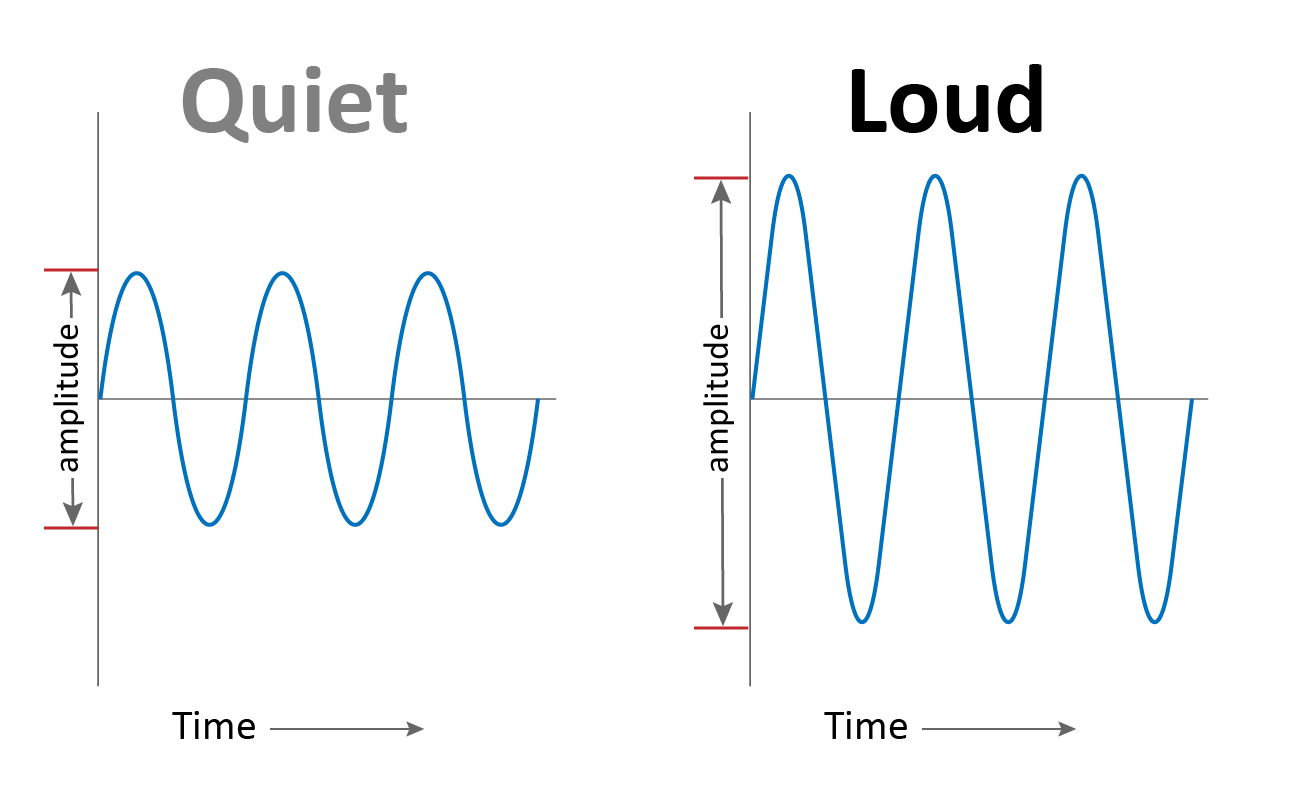

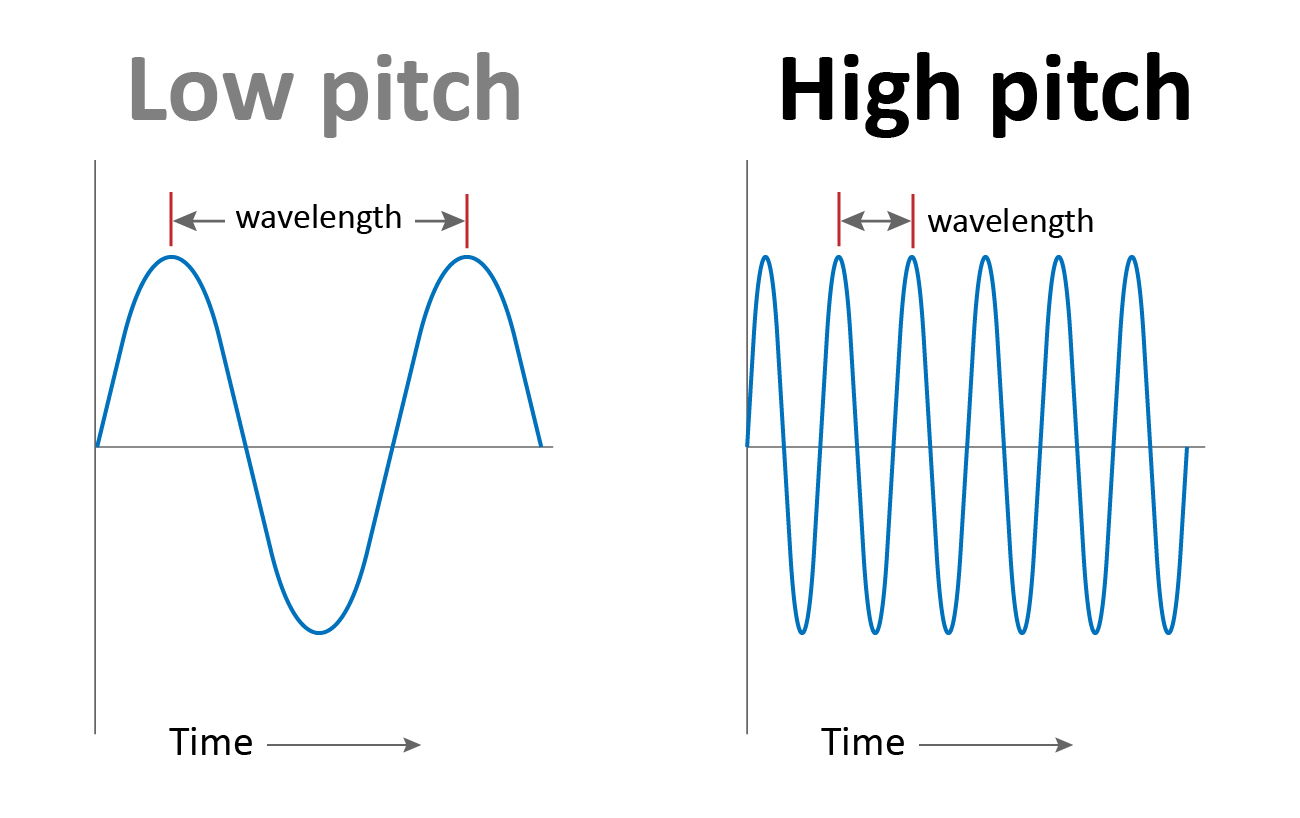

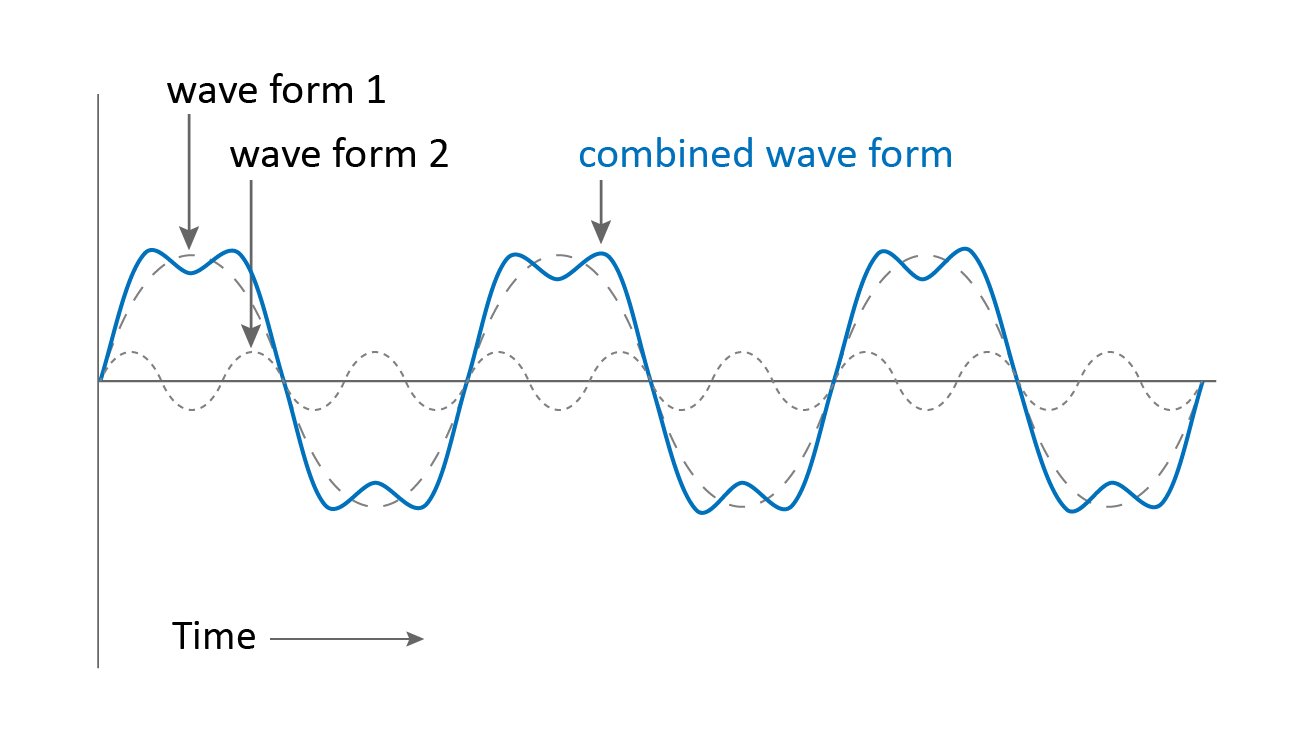

Sound is a series of pressure waves. Sound waves are made by objects that are vibrating. The vibrating object pushes on the air around it. Those air molecules bump into more-distant air molecules, setting up a chain reaction that carries the wave outward in all directions.

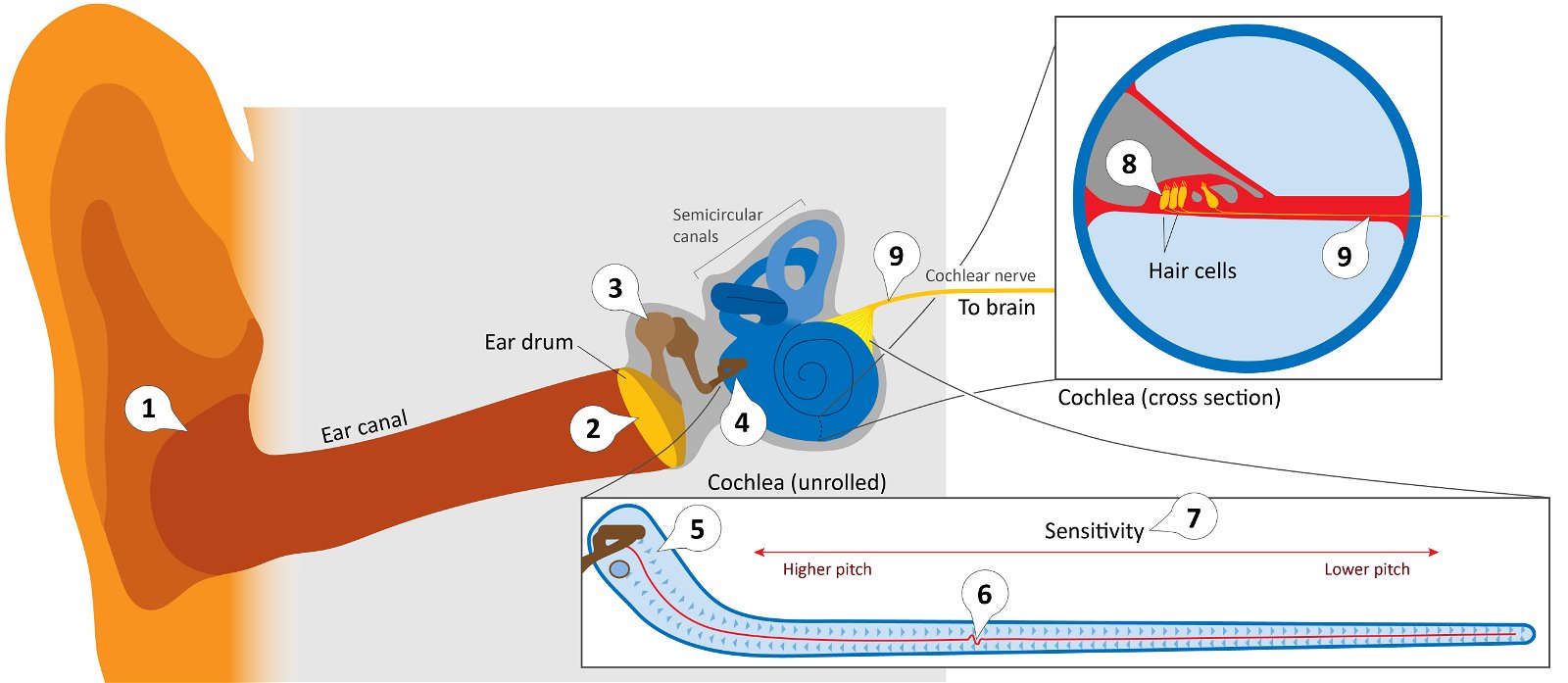

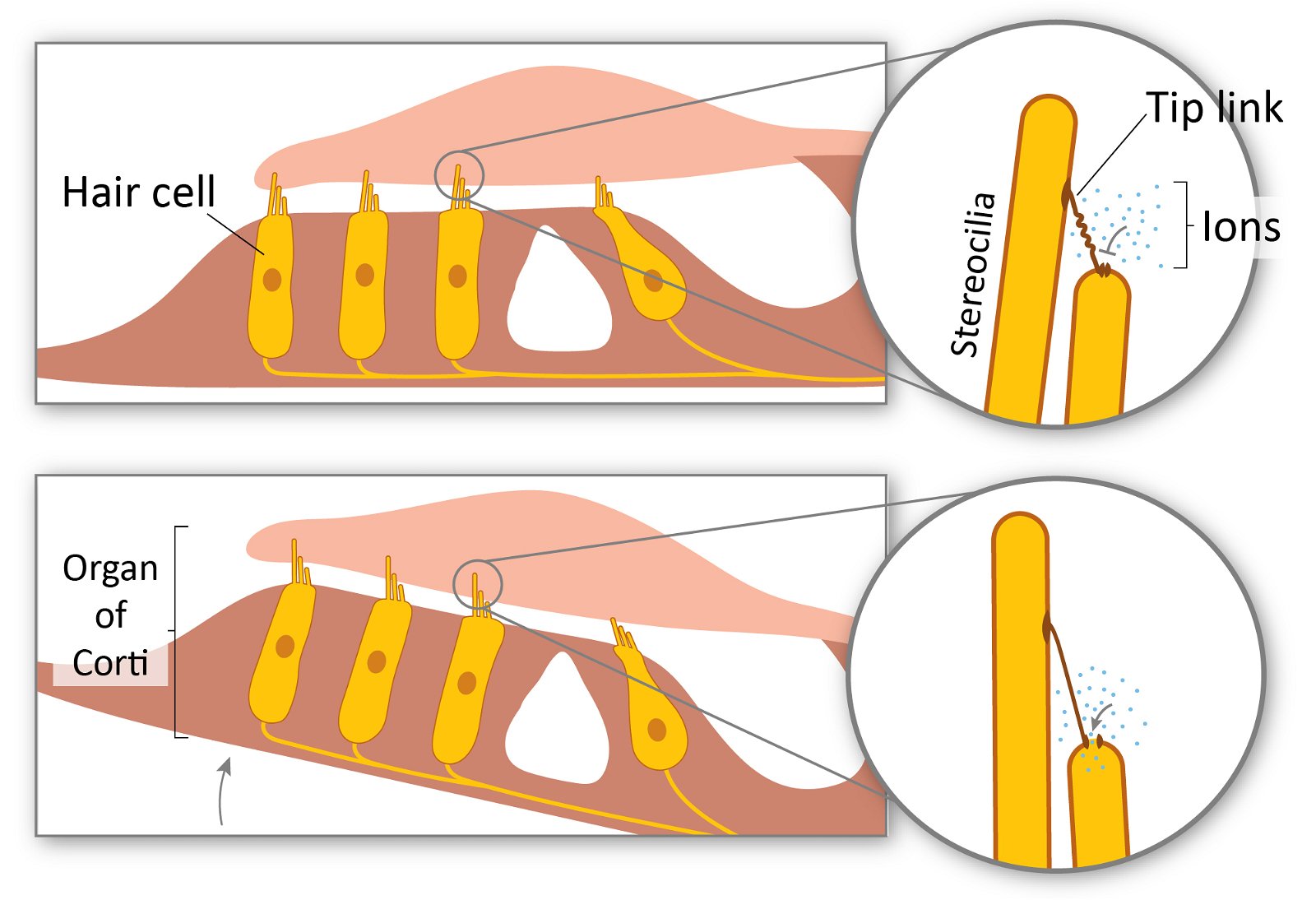

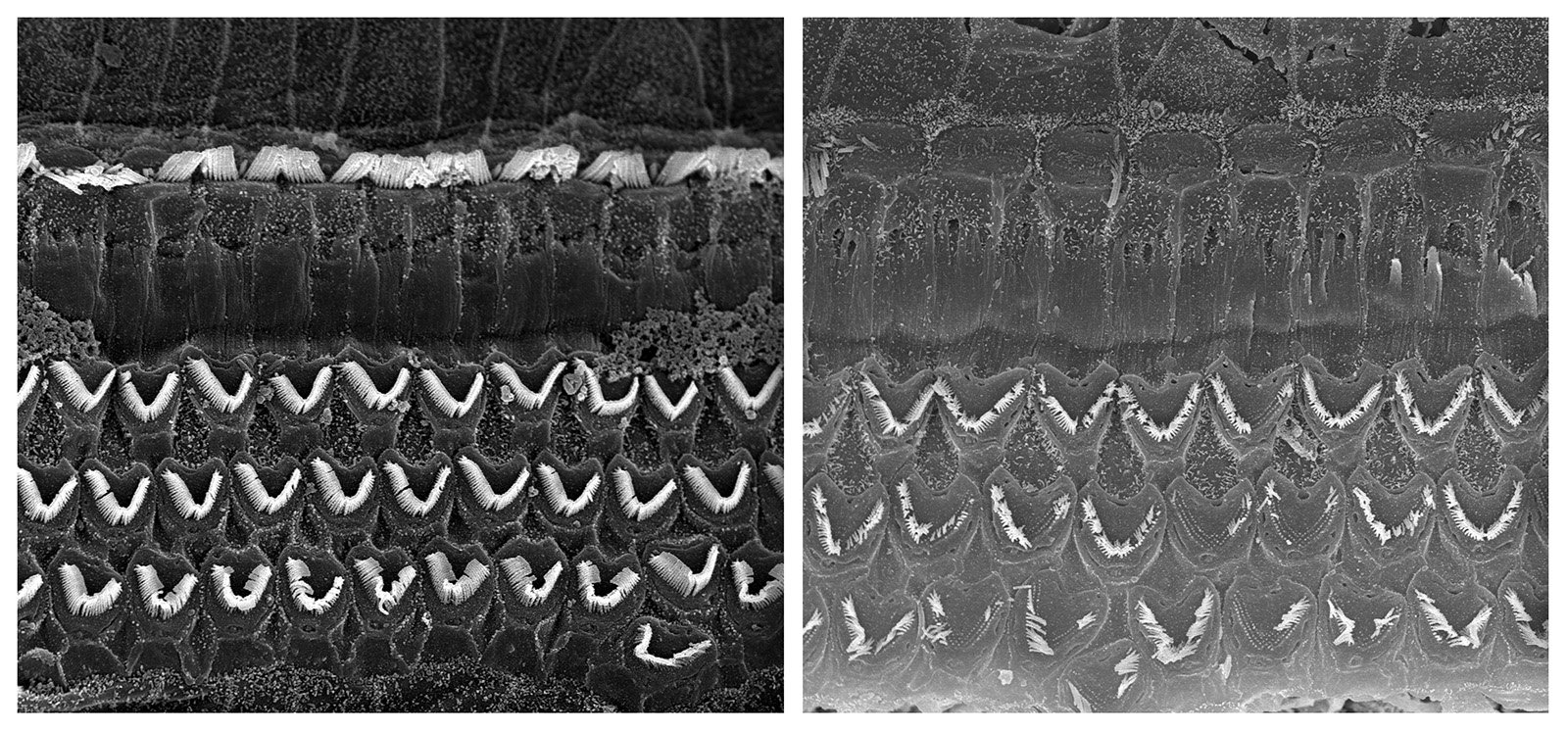

Our ears are filled with intricately moving parts that convert these mechanical waves into nerve signals that travel to the brain.

Just like waves spreading out from a pebble dropped into a puddle, sound waves travel out from their source, growing smaller as they get farther away.